On Style by Jonathan Swift

The following letter has laid before me many great and manifest evils in the world of letters which I had overlooked; but they open to me a very busy scene, and it will require no small care and application to amend errors which are become so universal. The affectation of politeness is exposed in this epistle with a great deal of wit and discernment; so that whatever discourses I may fall into hereafter upon the subjects the writer treats of, I shall at present lay the matter before the world without the least alteration from the words of my correspondent.

To Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq.

“Sir,

“There are some abuses among us of great consequence, the reformation of which is properly your province; though as far as I have been conversant in your papers, you have not yet considered them. These are the deplorable ignorance that for some years hath reigned among our English writers, the great depravity of our taste, and the continual corruption of our style. I say nothing here of those who handle particular sciences, divinity, law, physic, and the like; I mean the traders in history and politics, and the belles lettres; together with those by whom books are not translated, but (as the common expressions are) done out of French, Latin, or other language, and made English. I cannot but observe to you, that till of late years a Grub Street book was always bound in sheepskin, with suitable print and paper, the price never above a shilling, and taken off wholly by common tradesmen or country pedlars; but now they appear in all sizes and shapes, and in all places. They are handed about from lapfuls in every coffee-house to persons of quality; are shown in Westminster Hall and the Court of Requests. You may see them gilt and in royal paper of five or six hundred pages, and rated accordingly. I would engage to furnish you with a catalogue of English books published within the compass of seven years past, which at the first hand would cost you a hundred pounds, wherein you shall not be able to find ten lines together of common grammar or common sense.

“These two evils, ignorance and want of taste, have produced a third; I mean the continual corruption of our English tongue, which, without some timely remedy, will suffer more by the false refinements of twenty years past than it hath been improved in the foregoing hundred. And this is what I design chiefly to enlarge upon, leaving the former evils to your animadversion.

“But instead of giving you a list of the late refinements crept into our language, I here send you the copy of a letter I received some time ago from a most accomplished person in this way of writing; upon which I shall make some remarks. It is in these terms:

“‘Sir,

“‘Icou’dn’t get the things you sent for all about town. I thôt to ha’ come down myself, and then I’d h’ bôt ‘um; but I ha’n’t don’t, and I believe I can’t d’t, that’s pozz. Tom[121] begins to gi’mself airs, because he’s going with the plenipo’s. ‘Tis said the French King will bamboozl’ us agen, which causes many speculations. The Jacks and others of that kidney are very uppish, and alert upon’t, as you may see by their phizz’s. Will Hazzard has got the hipps, having lost to the tune of five hundr’d pound, thô he understands play very well, nobody better. He has promis’t me upon rep, to leave off play; but you know ’tis a weakness he’s too apt to give into, thô he has as much wit as any man, nobody more. He has lain incog. ever since. The mobb’s very quiet with us now. I believe you thôt I bantr’d you in my last like a country put. I shan’t leave town this month,’ &c.

“This letter is in every point an admirable pattern of the present polite way of writing, nor is it of less authority for being an epistle: you may gather every flower in it, with a thousand more of equal sweetness, from the books, pamphlets, and single papers, offered us every day in the coffee-houses: and these are the beauties introduced to supply the want of wit, sense, humour, and learning, which formerly were looked upon as qualifications for a writer. If a man of wit, who died forty years ago, were to rise from the grave on purpose, how would he be able to read this letter? And after he had got through that difficulty, how would he be able to understand it? The first thing that strikes your eye is the breaks at the end of almost every sentence, of which I know not the use, only that it is a refinement, and very frequently practised. Then you will observe the abbreviations and elisions, by which consonants of most obdurate sound are joined together, without one softening vowel to intervene; and all this only to make one syllable of two, directly contrary to the example of the Greeks and Romans, altogether of the Gothic strain, and a natural tendency towards relapsing into barbarity, which delights in monosyllables, and uniting of mute consonants, as it is observable in all the Northern languages. And this is still more visible in the next refinement, which consists in pronouncing the first syllable in a word that has many, and dismissing the rest; such as phizz, hipps, mobb, pozz, rep, and many more, when we are already overloaded with monosyllables, which are the disgrace of our language. Thus we cram one syllable, and cut off the rest, as the owl fattened her mice after she had bit off their legs, to prevent them from running away; and if ours be the same reason for maiming our words, it will certainly answer the end, for I am sure no other nation will desire to borrow them. Some words are hitherto but fairly split, and therefore only in their way to perfection, as incog. and plenipo; but in a short time, ’tis to be hoped, they will be further docked to inc. and plen. This reflection has made me of late years very impatient for a peace, which I believe would save the lives of many brave words, as well as men. The war has introduced abundance of polysyllables, which will never be able to live many more campaigns. Speculations, operations, preliminaries, ambassadors, palisadoes, communication, circumvallation, battalions, as numerous as they are, if they attack us too frequently in our coffee-houses, we shall certainly put them to flight, and cut off the rear.

“The third refinement observable in the letter I send you, consists in the choice of certain words invented by some pretty fellows, such as banter, bamboozle, country put, and kidney, as it is there applied, some of which are now struggling for the vogue, and others are in possession of it. I have done my utmost for some years past to stop the progress of mobb and banter, but have been plainly borne down by numbers, and betrayed by those who promised to assist me.

“In the last place, you are to take notice of certain choice phrases scattered through the letter, some of them tolerable enough, till they were worn to rags by servile imitators. You might easily find them, though they were not in a different print, and therefore I need not disturb them.

“These are the false refinements in our style which you ought to correct: first, by argument and fair means; but if those fail, I think you are to make use of your authority as censor, and by an annual ‘Index Expurgatorius’ expunge all words and phrases that are offensive to good sense, and condemn those barbarous mutilations of vowels and syllables. In this last point the usual pretence is, that they spell as they speak: a noble standard for language! To depend upon the caprice of every coxcomb, who, because words are the clothing of our thoughts, cuts them out and shapes them as he pleases, and changes them oftener than his dress. I believe all reasonable people would be content that such refiners were more sparing in their words and liberal in their syllables: and upon this head I should be glad you would bestow some advice upon several young readers in our churches, who coming up from the university full fraught with admiration of our town politeness, will needs correct the style of their prayer-books. In reading the Absolution, they are very careful to say ‘pardons’ and ‘absolves’; and in the prayer for the royal family it must be ‘endue ‘um, enrich ‘um, prosper ‘um, and bring ‘um.’ Then in their sermons they use all the modern terms of art: sham, banter, mob, bubble, bully, cutting, shuffling, and palming; all which, and many more of the like stamp, as I have heard them often in the pulpit from such young sophisters, so I have read them in some of those sermons that have made most noise of late. The design, it seems, is to avoid the dreadful imputation of pedantry; to show us that they know the town, understand men and manners, and have not been poring upon old unfashionable books in the university.

“I should be glad to see you the instrument of introducing into our style that simplicity which is the best and truest ornament of most things in life, which the politer ages always aimed at in their building and dress (simplex munditiis), as well as their productions of wit. It is manifest, that all new affected modes of speech, whether borrowed from the court, the town, or the theatre, are the first perishing parts in any language; and, as I could prove by many hundred instances, have been so in ours. The writings of Hooker, who was a country clergyman, and of Parsons the Jesuit, both in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, are in a style that, with very few allowances, would not offend any present reader; much more clear and intelligible than those of Sir H. Wootton, Sir Rob. Naunton, Osborn, Daniel the historian, and several others who wrote later; but being men of the court, and affecting the phrases then in fashion, they are often either not to be understood, or appear perfectly ridiculous.

“What remedies are to be applied to these evils, I have not room to consider, having, I fear, already taken up most of your paper. Besides, I think it is our office only to represent abuses, and yours to redress them. I am with great respect,

“Sir,

Your, &c.”

Summary

On Style by Jonathan Swift was first published in 1708 as part of The Tatler, a periodical founded by Richard Steele. Specifically, it appeared in The Tatler No. 230, dated September 23–26, 1710, under the pseudonym Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq. The essay was presented as a letter addressed to Bickerstaff, Swift’s fictional persona, and was later included in collections of Swift’s works, such as Miscellanies in Prose and Verse (1711). The Tatler was a widely read publication in early 18th-century London, circulating among coffee-house patrons and the literary elite, which amplified the essay’s reach and influence..

On Style by Jonathan Swift, written in 1708 and published in The Tatler as a letter to the fictional Isaac Bickerstaff, is a clever attack on the poor quality of English writing during Swift’s time. Swift, pretending to be an anonymous writer, complains that English books and papers have gotten much worse because of three big problems. First, many writers, especially those working on history, politics, or literature, are ignorant and don’t know enough to write well. Second, people have terrible taste, meaning they like and buy badly written books that lack good ideas or proper grammar.

Third, and worst of all, the English language itself is being ruined by trendy habits that make writing confusing and sloppy. These habits include using abbreviations like Icou’dn’t instead of I couldn’t, slang words like mobb for mob or pozz for positive, and chopping long words into short ones, such as phizz for physiognomy or hipps for hypochondria. Swift believes these changes make English less clear and elegant than it was in the past, undoing a hundred years of improvement in just twenty years.

To show how bad this “polite” writing style is, Swift includes a fake letter that’s full of mistakes on purpose. The letter uses messy sentences, trendy slang like bamboozle (to trick) and banter (teasing), and abbreviations like thôt for thought or bôt for bought. It jumps from one silly topic to another, talking about gossip, gambling, and politics in a shallow way, sounding like a fashionable city person trying to seem smart but failing.

Swift sarcastically calls this letter a great example of modern writing to make fun of how ridiculous it is. He points out specific problems: the letter has weird pauses after almost every sentence for no reason, it smashes harsh consonants together without vowels to make words shorter, and it cuts long words down to single syllables, which he compares to an owl biting off mice’s legs to keep them from running away. He also mocks new slang words like country put (a foolish rural person) and overused phrases that have lost all meaning because too many people copy them.

Swift doesn’t stop with books and papers. He also criticizes young preachers fresh from university who think they need to sound trendy to fit in with city folks. They use slang like sham (fake) or bubble (scam) in their sermons and change formal prayers, saying things like “endue ‘um” instead of “endue them” when praying for the royal family. Swift thinks this is absurd because it makes serious religious moments sound casual and silly, all to avoid seeming boring or overly scholarly. He sees this as part of a bigger problem where people value looking cool over communicating clearly.

To fix these issues, Swift urges Bickerstaff to step in as a kind of language police. He suggests first trying to convince writers to stop using bad habits through fair arguments. If that doesn’t work, Bickerstaff should use his authority to ban confusing words and phrases, maybe by making a yearly list called an Index Expurgatorius, like a rulebook of what not to say. Swift is half-joking here, but he’s serious about wanting better writing.

He praises older writers from Queen Elizabeth’s time, like Richard Hooker, whose clear style still makes sense today, unlike later writers like Sir H. Wootton, whose trendy phrases now seem unclear or laughable. Swift believes good writing should be simple and straightforward, not packed with fads that make it hard to understand.

At the end, Swift’s fake correspondent says they don’t have space to list solutions and that it’s Bickerstaff’s job to fix things, not just point them out. The letter closes politely, keeping up the act of a formal complaint.

Essay Analysis

The following letter has laid ………………….. of my correspondent.

Summary: The letter I got points out big problems in writing that I hadn’t noticed before. It shows a messy situation, and fixing these widespread mistakes will take a lot of effort. The letter cleverly mocks the fake politeness in today’s writing with sharp wit. For now, I’m sharing the letter exactly as written, without changing a word, to let everyone see these issues. I’ll talk more about these topics later.

Analysis: This paragraph, from Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), introduces a letter Swift (as Isaac Bickerstaff) claims to have received, which highlights problems in English writing.

To Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq. ……………………………………….together of common grammar or common sense.

Summary: Dear Mr. Bickerstaff,

There are some serious problems in our society that you, as a writer and critic, should address. You haven’t talked about these issues in your papers yet, but they’re a big deal. English writers have become really ignorant lately, our taste in writing is awful, and the way we write—our style—keeps getting worse. I’m not talking about people who write about specialized topics like religion, law, or medicine. I mean those who write about history, politics, or literature, as well as people who don’t properly translate books from French, Latin, or other languages but just rewrite them poorly into English.

I’ve noticed something else: until recently, cheap books from Grub Street (where hack writers work) were simple—bound in sheepskin, printed on basic paper, and sold for a shilling to tradesmen or rural peddlers. But now, these books come in all sorts of fancy formats and are everywhere. You see them piled up in coffee-houses, passed around to important people, and even displayed in places like Westminster Hall and the Court of Requests.

Some are bound in gold, printed on fancy paper, and stretch to 500 or 600 pages, with prices to match. I could give you a list of English books from the last seven years that would cost £100 to buy, but you wouldn’t find even ten lines in them with proper grammar or good sense.

Analysis:

Isaac Bickerstaff: Swift’s fictional persona, a critic and commentator in The Tatler, who the letter is addressing.

“Abuses”: The letter writer is pointing out major flaws in English writing, calling them “abuses” to emphasize their severity.

Three Problems: The writer highlights ignorance (lack of knowledge), bad taste (poor judgment in what’s good), and corrupt style (sloppy or trendy writing) as widespread issues.

Focus on Certain Writers: The complaint targets writers of history, politics, and literature (belles lettres), not those in technical fields like law or medicine. It also criticizes lazy translators who churn out bad English versions of foreign books.

Grub Street Books: Grub Street was a term for low-quality, hack writing. These books used to be cheap and sold to working-class people, but now they’re dressed up expensively and marketed to elites in fashionable places like coffee-houses and courts.

Lack of Quality: The writer claims that despite their fancy appearance, these books are so poorly written that you can’t find even a few lines with correct grammar or clear ideas.

“These two evils, ignorance and want of taste ……………………………………….former evils to your animadversion.

Summary: In this paragraph from Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), the fictional correspondent writing to Isaac Bickerstaff explains how two problems in English writing lead to a third, even bigger issue.

The two problems—ignorance (writers not knowing enough) and bad taste (liking poor-quality writing)—have caused a third issue: the English language is getting worse and worse. If we don’t fix this soon, the damage done by the trendy but bad changes in the last 20 years will outweigh the progress made in the previous 100 years. I’m going to focus on explaining this language problem in detail, and I’ll leave the issues of ignorance and bad taste for you to criticize.

Analysis:

“Two evils”: Ignorance (lack of knowledge) and want of taste (poor judgment in writing) are the root causes.

“Third” issue: These problems are ruining the English language itself, making it less clear and effective.

“False refinements”: The writer refers to trendy changes, like slang and abbreviations, which they see as harmful rather than helpful.

“Twenty years past” vs. “foregoing hundred”: The last 20 years (roughly 1688–1708) have introduced bad trends that threaten to undo a century of improvement in English (1588–1688).

“Timely remedy”: The writer stresses the need for quick action to stop the decline.

“Enlarge upon”: The correspondent plans to focus on the language issue.

“Animadversion”: This means criticism, so the writer is leaving it to Bickerstaff to address ignorance and bad taste.

“But instead of giving ………………………………………. It is in these terms:

Summary: In this paragraph from Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), the fictional correspondent writing to Isaac Bickerstaff introduces a satirical letter to illustrate the problems with English writing.

Instead of listing all the trendy but bad changes that have snuck into our language, I’m sharing a letter I got a while ago from someone who’s really good at this awful style of writing. I’ll add some comments about it. Here’s what the letter says:

Analysis:

“Late refinements”: Refers to new, fashionable ways of writing (like slang and abbreviations) that the writer sees as harmful.

“Crept into our language”: Suggests these changes have quietly and sneakily become common.

“Copy of a letter”: The correspondent is presenting a fake letter (likely written by Swift himself) as an example of bad writing.

“Most accomplished person”: This is sarcastic—Swift is mocking the writer of the letter, implying they’re skilled at using this terrible style.

“Make some remarks”: The correspondent will analyze the letter to point out its flaws.

“It is in these terms”: Introduces the letter itself, which follows in the essay.

“‘Sir, “‘Icou’dn’t get the things ………………………………………. shan’t leave town this month,’ &c.

Summary: This is the satirical letter included in Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), written by a fictional correspondent to Isaac Bickerstaff. Swift uses it to mock the trendy, sloppy writing style of his time.

Dear Sir,

I couldn’t find the things you asked for anywhere in town. I thought about coming down myself to buy them, but I haven’t done it, and I’m pretty sure I can’t, for sure. Tom is acting all high and mighty because he’s hanging out with diplomats. People say the French King is going to trick us again, which is causing a lot of gossip. The radicals and similar folks are acting cocky and on edge, and you can tell by their faces.

Will Hazzard is super depressed because he lost £500 gambling, even though he’s really good at it, better than anyone. He promised me on his reputation that he’ll quit gambling, but you know he’s weak and keeps doing it, even though he’s as smart as anyone, maybe smarter. He’s been hiding out ever since. The crowd around here is calm now. I bet you thought I was joking in my last letter, like some clueless country bumpkin. I’m not leaving town this month.

Analysis: This letter is deliberately written in a bad style to show what Swift hates about contemporary English. Here’s why it’s a mess:

Abbreviations: Words like Icou’dn’t (I couldn’t), thôt (thought), ha’ (have), bôt (bought), and d’t (do it) are shortened in a sloppy, trendy way, making the letter hard to read.

Slang: Terms like pozz (positive/for sure), bamboozl’ (bamboozle, to trick), uppish (arrogant), phizz’s (faces, from physiognomy), hipps (hypochondria/depression), rep (reputation), incog. (incognito), mobb (mob), and bantr’d (bantered/teased) are fashionable but vague or silly.

Weird Phrases: Expressions like “others of that kidney” (people like that), “to the tune of” (amounting to), and “country put” (a foolish rural person) are trendy but unclear or overused.

Choppy Sentences: The letter jumps around with short, broken sentences, lacking flow or clarity.

Gossip and Name-Dropping: Mentioning “Tom,” “plenipo’s” (plenipotentiaries/diplomats), “the French King,” “the Jacks” (likely Jacobites or radicals), and “Will Hazzard” mimics shallow, gossipy talk instead of meaningful writing.

Swift uses this letter to exaggerate the flaws he’s criticizing: ignorance, bad taste, and corrupted language. It’s meant to sound ridiculous to prove his point that English writing is becoming unclear and full of pointless trends. The letter continues with “&c.” (etc.), suggesting more of the same nonsense, but Swift stops here to analyze it in the next part of the essay.

“This letter is in every point ………………………………………. put them to flight, and cut off the rear.

Summary: This paragraph from Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), part of the letter to Isaac Bickerstaff, analyzes the satirical letter Swift included earlier to mock the trendy, sloppy writing style of his time.

This letter is a perfect example of the so-called “polite” writing style that’s popular now, and being a letter doesn’t make it any less typical. You can find the same flashy but empty language in books, pamphlets, and papers passed around in coffee-houses every day. These are the “beauties” people use to cover up their lack of wit, common sense, humor, or knowledge—things good writers used to have. Imagine a clever person who died 40 years ago coming back to life: they’d struggle to read this letter, and even if they could, they wouldn’t understand it!

The first thing you notice is how the sentences are broken up with pauses at the end of almost every line, for no clear reason except it’s a trendy habit. Then there are the abbreviations, where harsh consonants are smashed together without vowels to soften them, just to turn two syllables into one. This goes against the clear, flowing style of ancient Greek and Roman writing and feels like a step back to crude, Northern European languages that love short, choppy words and clunky consonants. Even worse, people take long words and use only the first syllable, like phizz (for face), hipps (for depression), mobb (for mob), pozz (for positive), and rep (for reputation). English already has too many short, ugly words, and this habit makes it worse. It’s like an owl biting off mice’s legs to keep them from running away—if we’re chopping words like this to keep them short, it works, because no other country will want to use them!

Some words, like incog. (incognito) and plenipo (plenipotentiary), are only partly shortened but heading toward being even briefer, like inc. or plen. I’ve been hoping for peace lately, because war brings long, fancy words like speculations, operations, preliminaries, ambassadors, palisadoes, communication, circumvallation, and battalions. These words won’t last long if they keep showing up in coffee-house chatter—we’ll chop them down or get rid of them entirely.

Analysis:

“Admirable pattern”: Sarcastic—Swift calls the letter a great example of bad writing to mock it.

“Polite way of writing”: Refers to the trendy, fashionable style that Swift thinks is shallow and poorly done.

Coffee-house materials: The same bad style is in everyday publications, showing how widespread the problem is.

Lack of “wit, sense, humour, and learning”: Swift says modern writers use flashy language to hide that they’re not smart, funny, or educated, unlike past writers.

Imagery of a resurrected person: A clever person from 1668 would find the letter’s style (full of slang and abbreviations) unreadable and incomprehensible, showing how much English has declined.

Sentence breaks: The letter’s choppy structure, with pauses after nearly every sentence, is a pointless trend Swift doesn’t understand.

Abbreviations and elisions: Words like Icou’dn’t or ha’ mash consonants together without vowels, making them harsh and short, unlike the smoother Greek and Roman styles.

“Gothic strain”: Swift compares this to Northern European languages (e.g., Germanic ones), which he sees as crude for favoring monosyllables and rough sounds.

Shortened words: Examples like phizz, hipps, mobb, pozz, and rep show how writers cut long words to single syllables, which Swift thinks makes English uglier.

Owl analogy: Cutting words down is like an owl biting off mice’s legs—effective but brutal, ensuring no one else will want these “maimed” words.

Words in progress: Incog. and plenipo are halfway to being even shorter (inc., plen.), showing the trend is ongoing.

War and polysyllables: The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) brought long, technical words into English, but Swift predicts they’ll be shortened or forgotten in casual settings like coffee-houses.

Military metaphor: Swift humorously says these long words will be “attacked” and “cut off” by the trend of simplifying language.

This paragraph is Swift’s sharp, witty critique of how trendy writing habits—choppy sentences, abbreviations, and slang—are ruining English, making it less clear and elegant than it used to be.

“The third refinement observable ………………………………………. who promised to assist me.

Summary: In this paragraph from Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), part of the letter to Isaac Bickerstaff, the fictional correspondent continues analyzing the satirical letter, focusing on a third problematic trend in English writing.

The third trendy habit in the letter I sent you is the use of silly new words made up by some clever guys, like banter (teasing or joking), bamboozle (to trick or confuse), country put (a foolish rural person), and kidney (used to mean “type” or “kind,” as in “people of that kidney”). Some of these words are just starting to catch on, while others are already super popular. For years, I’ve tried hard to stop words like mobb (mob) and banter from spreading, but too many people use them, and even those who promised to help me fight these words let me down.

Analysis:

“Third refinement”: The correspondent is pointing out another fashionable but bad writing habit (after choppy sentences and abbreviations).

“Certain words invented”: Refers to slang terms like banter, bamboozle, country put, and kidney (used to mean “type”), which Swift sees as silly and unnecessary.

“Pretty fellows”: Sarcastic—Swift mocks the people who create these trendy words, implying they think they’re clever but aren’t.

“Struggling for the vogue” vs. “in possession of it”: Some words are still trying to become popular, while others are already widely used.

“Stop the progress of mobb and banter”: The correspondent (Swift’s voice) claims to have fought against slang like mobb and banter for years, showing Swift’s personal dislike for these terms.

“Borne down by numbers”: Too many people use these words, so the fight to stop them has failed.

“Betrayed by those who promised to assist”: Others who agreed to help resist these slang terms didn’t follow through, leaving the correspondent (Swift) frustrated.

This paragraph highlights Swift’s annoyance with trendy slang, which he sees as lowering the quality of English by replacing meaningful words with vague, fashionable ones. It also shows his satirical tone, pretending to be a lone crusader against bad language while poking fun at the trendsetters.

“In the last place, ………………………………………. need not disturb them.

Summary: In this paragraph from Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), part of the letter to Isaac Bickerstaff, the fictional correspondent points out a final issue with the satirical letter’s writing style.

Finally, you should notice some catchy phrases sprinkled throughout the letter. Some of these were okay at first, but they’ve been overused by copycats until they’re completely worn out. You can spot them easily, even without me pointing them out, so I won’t bother listing them.

Analysis:

“In the last place”: This signals the final point the correspondent is making about the letter’s flaws.

“Certain choice phrases”: Refers to trendy expressions in the letter, like “to the tune of” (meaning “amounting to”) or “of that kidney” (meaning “that type”), which Swift finds annoying.

“Tolerable enough”: Some phrases were decent when first used, but Swift implies they were never great.

“Worn to rags by servile imitators”: These phrases have been used so much by unoriginal writers that they’ve lost all freshness or meaning, like tattered clothes.

“Easily find them”: The phrases stand out obviously in the letter, so there’s no need to highlight them (unlike in some editions where they might be in different print, like italics).

“Need not disturb them”: The correspondent (Swift) decides not to list the phrases, trusting Bickerstaff (and readers) to notice them.

This paragraph wraps up Swift’s critique of the letter’s style, poking fun at overused expressions that have become clichés. It shows his disdain for writers who lazily repeat trendy phrases instead of creating original, meaningful ones.

“These are the false refinements ………………………………………. old unfashionable books in the university.

Summary: In this paragraph from Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), part of the letter to Isaac Bickerstaff, the fictional correspondent urges Bickerstaff to fix the problematic trends in English writing and criticizes those who justify these trends.

These trendy but bad writing habits—choppy sentences, abbreviations, slang, and overused phrases—are what you need to fix. First, try reasoning with people to change their ways. If that doesn’t work, use your authority as a critic to ban words and phrases that don’t make sense, maybe by making a yearly list called an Index Expurgatorius to get rid of these awful changes, like chopping up vowels and syllables.

People claim they write this way because “that’s how they speak,” but that’s a terrible excuse for language! It’s like letting every vain fool cut and shape words however they want, changing them as often as they change their clothes. Sensible people would prefer these writers use fewer words but keep more syllables to make things clearer.

I’d also love for you to advise young church readers, especially those fresh from university who are obsessed with trendy city manners. They think they need to “fix” the prayer books! When reading the Absolution, they say “pardons” and “absolves” in a fancy way. In prayers for the royal family, they say “endue ‘um,” “enrich ‘um,” “prosper ‘um,” and “bring ‘um,” sounding sloppy.

In their sermons, they throw in modern slang like sham (fake), banter (teasing), mob (crowd), bubble (scam), bully (intimidator), cutting (cheating), shuffling (deceiving), and palming (sleight of hand). I’ve heard these words from young, show-off preachers and seen them in their popular sermons. They do this to avoid seeming boring or old-fashioned, to prove they’re in touch with city life and not just stuck reading outdated university books.

Analysis:

“False refinements”: Refers to the bad writing trends Swift criticized earlier: choppy sentences, abbreviations (e.g., Icou’dn’t), slang (e.g., mobb, banter), and overused phrases.

“Correct”: The correspondent wants Bickerstaff to stop these trends.

“Argument and fair means”: Try persuading people logically first.

“Authority as censor”: If persuasion fails, Bickerstaff should act like an official critic and ban bad words.

“Index Expurgatorius”: A satirical idea for a yearly list of banned words and phrases, mimicking Catholic lists of forbidden books, to eliminate senseless language.

“Barbarous mutilations”: Refers to chopping words (e.g., phizz for physiognomy) by removing vowels or syllables, which Swift sees as crude.

“Spell as they speak”: Writers justify their sloppy style by saying it matches casual speech, but Swift mocks this as a weak excuse.

“Caprice of every coxcomb”: Swift insults these writers as vain fools (coxcombs) who treat words like fashion, changing them on a whim.

“More sparing in their words and liberal in their syllables”: Swift wants writers to use fewer but fuller words (e.g., physiognomy instead of phizz) for clarity.

Young church readers: Swift targets young clergy fresh from university, influenced by trendy urban culture.

Prayer book changes: These clergy mispronounce or abbreviate words in prayers (e.g., “endue ‘um” instead of “endue them”) to sound fashionable.

Sermon slang: They use trendy terms like sham, banter, and mob in sermons to seem modern and avoid being called pedantic (overly scholarly).

“Know the town”: They want to show they’re savvy about city life, not just bookish scholars.

Satirical tone: Swift mocks these young preachers as shallow, chasing trends to seem cool rather than focusing on clear, meaningful communication.

This paragraph sums up Swift’s call to action and extends his critique to young clergy, showing how the trendy writing style has even invaded serious contexts like church sermons, driven by a desire to appear fashionable.

“I should be glad to see ………………………………………. or appear perfectly ridiculous.

Summary: In this paragraph from Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), part of the letter to Isaac Bickerstaff, the fictional correspondent expresses a desire for simpler writing and criticizes trendy speech.

I’d love for you to help bring back a simple writing style, which is the best and truest way to make things beautiful, just like in life—whether it’s buildings, clothes, or clever writing. The most refined times always aimed for this kind of elegant simplicity (simplex munditiis). It’s obvious that trendy, fake ways of talking—picked up from the royal court, city life, or theaters—are the first parts of a language to die out. I could show you hundreds of examples proving this in English.

Take the writings of Hooker, a country priest, and Parsons, a Jesuit, from Queen Elizabeth’s time. Their style is so clear that, with a few tweaks, it would still make sense to readers today. But writers like Sir H. Wootton, Sir Rob. Naunton, Osborn, Daniel the historian, and others who came later wrote in a way that’s often confusing or just laughable. They were court insiders who used trendy phrases of their time, which now sound outdated or silly.

Analysis:

“Instrument of introducing”: The correspondent wants Bickerstaff to lead the charge in promoting a better writing style.

“Simplicity”: Swift praises plain, clear writing as the best way to communicate, comparing it to beauty in other areas of life.

“Best and truest ornament”: Simplicity is like a timeless decoration that makes writing (and other things) genuinely appealing.

“Politer ages”: Refers to past eras (like ancient Greece, Rome, or Elizabethan England) that valued elegant simplicity in architecture, fashion, and wit.

“Simplex munditiis”: A Latin phrase from Horace meaning “simple elegance,” reinforcing Swift’s point about refined simplicity.

“New affected modes of speech”: Trendy, artificial ways of talking from places like the court (royalty), town (urban society), or theater are criticized as shallow.

“First perishing parts”: These trendy phrases fade quickly, unlike clear, simple language that lasts.

Historical examples:

Hooker and Parsons: Richard Hooker (Anglican theologian) and Robert Parsons (Jesuit priest), both from the late 1500s, wrote clearly in a style that’s still understandable today.

Wootton, Naunton, Osborn, Daniel: Later writers (early 1600s) like Henry Wotton (diplomat), Robert Naunton (politician), Francis Osborn (essayist), and Samuel Daniel (historian) used courtly, trendy phrases that now seem unclear or ridiculous.

Contrast: Hooker and Parsons, being less influenced by fashionable circles, wrote timelessly, while court-connected writers chased trends, making their work dated.

Swift is pushing for a return to clear, lasting language and warning that trendy speech, while popular, quickly becomes obsolete or absurd. He uses historical examples to show that simplicity outlasts fashion.

“What remedies are to be applied ………………………………………. with great respect,

“Sir,

“Your, &c.”

Summary: In this final paragraph from Jonathan Swift’s On Style (1708), part of the letter to Isaac Bickerstaff, the fictional correspondent wraps up their critique of English writing and passes the responsibility for solutions to Bickerstaff.

I don’t have space to suggest fixes for these writing problems, and I’m worried I’ve already used up most of your paper. Anyway, I think my job is just to point out what’s wrong, and it’s your job to fix it. With great respect,

Sir,

Yours, etc.

Analysis:

“What remedies”: The correspondent refers to solutions for the “evils” (bad writing trends like slang, abbreviations, and overused phrases) they’ve criticized throughout the letter.

“I have not room”: They claim there’s no space left to discuss solutions, a rhetorical way to avoid going into detail (and possibly a nod to the essay’s length).

“Taken up most of your paper”: A polite excuse, suggesting they’ve written too much already, fitting the formal tone of a letter.

“Our office only to represent abuses”: The correspondent says their role is to highlight problems, not solve them, framing themselves as an observer.

“Yours to redress them”: They place the responsibility on Bickerstaff (Swift’s persona) to correct these issues, likely a satirical way of urging action while maintaining the fiction of the letter.

“With great respect”: A formal closing, typical of 18th-century letters, showing courtesy to Bickerstaff.

“Your, &c.”: A standard sign-off, with “&c.” (etc.) implying the rest of a formal closing, like “Your humble servant.”

This closing reinforces the letter’s satirical tone: while the correspondent pretends to defer to Bickerstaff, Swift is subtly challenging readers and writers to reject trendy, sloppy language and embrace clarity. It also neatly concludes the critique by focusing on identifying problems rather than offering detailed solutions, keeping the essay sharp and focused.

Key Points

Author

Jonathan Swift (1667–1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, poet, and clergyman, best known for Gulliver’s Travels (1726). A master of satire, Swift used sharp wit to critique societal flaws, including politics, religion, and language. In On Style, published under the pseudonym Isaac Bickerstaff in The Tatler (No. 230, September 23–26, 1710), Swift adopts a fictional correspondent’s voice to mock poor writing trends, reflecting his lifelong concern with clear, effective language, as seen in works like A Proposal for Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining the English Tongue (1712).

Introduction

The essay begins with Swift, as Isaac Bickerstaff, introducing a letter he claims to have received, which exposes “great and manifest evils” in English writing that he had overlooked. He praises the letter’s witty critique of the “affectation of politeness” in contemporary style and promises to present it unchanged to inform the public. This sets a satirical tone, framing the letter as a serious complaint while hinting at Swift’s playful intent to mock bad writing through exaggeration.

Structure

On Style is structured as a single letter addressed to Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq., divided into distinct sections:

Introduction: Bickerstaff (Swift) explains the letter’s purpose and value (first paragraph).

Statement of Problems: The correspondent identifies three main issues—ignorance, bad taste, and the corruption of the English language—focusing on writers of history, politics, and literature (second paragraph).

Illustration via Satirical Letter: A mock letter is presented, filled with slang, abbreviations, and choppy sentences to exemplify bad writing.

Analysis of Flaws: The correspondent critiques the mock letter’s stylistic flaws:

Choppy sentence breaks, abbreviations, and monosyllables (e.g., phizz, mobb).

Trendy slang (e.g., banter, bamboozle).

Overused phrases worn out by imitators.

Call to Action: The correspondent urges Bickerstaff to correct these trends through persuasion or a satirical Index Expurgatorius (list of banned words) and criticizes young clergy for adopting slang in sermons (seventh paragraph).

Advocacy for Simplicity: The correspondent praises simple, timeless writing, citing Elizabethan writers like Hooker and Parsons, and contrasts them with later, trendy court writers (eighth paragraph).

Conclusion: The correspondent avoids suggesting detailed solutions, claiming it’s Bickerstaff’s job to fix the issues, and closes formally.

Setting

The essay is set in early 18th-century London, during a time of growing print culture and coffee-house debates. Published in The Tatler, a popular periodical, it reflects the literary and social environment of the Augustan Age, where writers like Swift, Steele, and Addison shaped public discourse. The letter references specific locations—coffee-houses, Westminster Hall, and the Court of Requests—where books and ideas circulated, highlighting the urban, intellectual context. The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) is mentioned, tying the essay to contemporary politics and its influence on language (e.g., war-related polysyllables like battalions).

Themes

Decline of Language: Swift laments the corruption of English through slang, abbreviations, and trendy phrases, arguing that these “false refinements” make writing unclear and inelegant, threatening a century of linguistic progress.

Simplicity vs. Affectation: He advocates for clear, simple writing as the ideal, contrasting it with the artificial, fashionable style driven by a desire to seem “polite” or modern.

Social Critique: The essay links bad writing to broader societal flaws, like vanity and shallow trend-chasing, especially among urban elites and young clergy who mimic city manners.

Cultural Conservatism: Swift’s preference for older, clearer writers (e.g., Hooker) and his resistance to linguistic change reflect a conservative view of language as a stable, refined tool.

Authority and Reform: The call for Bickerstaff to act as a “censor” with an Index Expurgatorius suggests a need for oversight to maintain linguistic standards, though presented satirically.

Style

Swift’s style in On Style is satirical, witty, and formal, blending humor with sharp criticism:

Satire: The mock letter exaggerates bad writing (e.g., Icou’dn’t, bamboozle) to ridicule trendy styles, while the correspondent’s earnest tone adds irony.

Irony: Phrases like “admirable pattern” for the terrible letter and the over-the-top Index Expurgatorius mock the very trends Swift critiques.

Formal Letter Format: The essay uses 18th-century epistolary conventions (e.g., “Dear Sir,” “Yours, &c.”) to maintain the fiction of a real correspondent.

Vivid Imagery: Analogies like the owl biting off mice’s legs (for word truncation) and words “worn to rags” make the critique memorable.

Historical References: Citing writers like Hooker and Wootton grounds the argument in literary history, appealing to educated readers.

Humorous Exaggeration: The idea that war-related words like battalions will be “put to flight” in coffee-houses adds a playful, military metaphor to the critique.

The style is accessible yet sophisticated, designed for Tatler’s literate audience, balancing entertainment with intellectual critique.

Message

Swift’s core message is that English writing is declining due to ignorance, bad taste, and trendy but sloppy language, and it needs to return to simplicity and clarity. He warns that fashionable slang, abbreviations, and overused phrases make communication unclear and short-lived, unlike the timeless style of earlier writers. By satirizing these trends and urging reform, Swift calls for writers to prioritize substance over style and for society to value clear, meaningful language. The essay also subtly critiques the vanity and superficiality driving these trends, suggesting that true elegance lies in simplicity, not affectation.

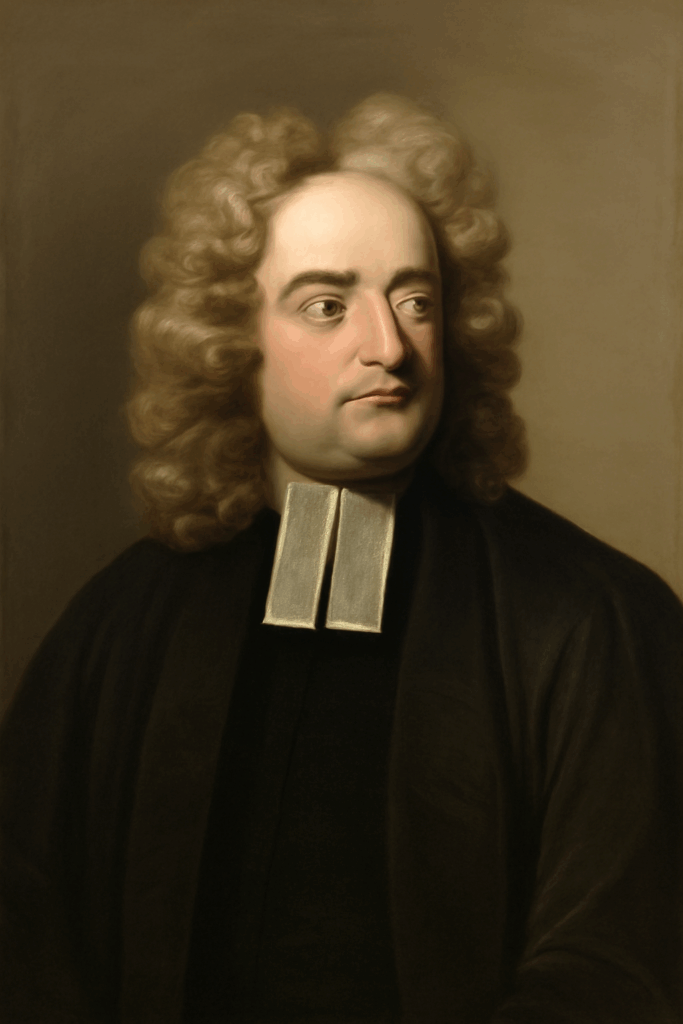

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (1667–1745) was an Anglo-Irish author, satirist, essayist, poet, and Anglican clergyman, widely regarded as one of the greatest prose satirists in the English language. Born in Dublin, Ireland, on November 30, 1667, to English parents, Swift’s life was shaped by his sharp intellect, biting wit, and complex relationship with both Ireland and England. Below is an overview of his life, career, and significance, tailored to provide a clear and concise understanding in the context of his essay On Style (1708).

Early Life and Education

Background: Swift’s father, Jonathan Swift Sr., died before his birth, leaving his mother, Abigail Erick, in financial strain. He was raised partly by his uncle, Godwin Swift, in Dublin and sent to live with relatives in England during Ireland’s political unrest in the 1670s.

Education: Swift attended Trinity College, Dublin, earning a Bachelor of Arts in 1686, though he later described his academic performance as lackluster. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 forced him to flee to England, where he pursued further studies at Oxford, earning a Master of Arts in 1692.

Early Career: In England, Swift worked as a secretary to Sir William Temple, a retired diplomat, at Moor Park, Surrey (1689–1694). This role exposed him to politics, literature, and influential figures, shaping his writing and worldview. He began writing poetry and prose during this period.

Literary Career

Major Works:

A Tale of a Tub (1704): A satirical allegory critiquing religious disputes and literary excesses, establishing Swift’s reputation for sharp wit.

The Battle of the Books (1704): A mock-epic defending classical literature against modern writers, reflecting his conservative literary tastes.

Gulliver’s Travels (1726): His most famous work, a satirical novel exploring human nature, politics, and society through fantastical voyages.

A Modest Proposal (1729): A darkly humorous essay proposing that Irish poor sell their children as food to the rich, critiquing British exploitation of Ireland.

On Style (1708): Published in The Tatler (No. 230, September 23–26, 1710) under the pseudonym Isaac Bickerstaff, this essay critiques the decline of English writing, advocating for clarity and simplicity.

Pseudonyms and Periodicals: Swift often wrote under pseudonyms, like Isaac Bickerstaff in The Tatler, a periodical he contributed to alongside Richard Steele and Joseph Addison. He also used the persona of M.B. Drapier in Drapier’s Letters (1724–1725) to oppose British economic policies in Ireland.

Style: Swift’s writing is defined by sharp satire, irony, and a conversational yet precise prose style. He used humor to expose societal flaws, blending wit with moral critique, as seen in On Style’s mock letter and exaggerated solutions like the Index Expurgatorius.

Clerical and Political Life

Ordination: Swift was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1695 and served in various parishes, including Kilroot, Ireland (1695–1696). In 1713, he became Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, a position he held until his death.

Politics: Swift was politically active, initially aligning with the Whigs but later switching to the Tories around 1710, reflecting his disillusionment with Whig policies. He wrote pamphlets and essays, like The Conduct of the Allies (1711), supporting Tory views during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), referenced in On Style’s mention of war-related words.

Irish Advocacy: Despite identifying as English, Swift became a defender of Irish interests, especially in the 1720s. His Drapier’s Letters and A Modest Proposal criticized British economic oppression and neglect of Ireland, earning him a reputation as an Irish patriot.

Context for On Style

Literary Environment: On Style was written during the Augustan Age, a period of refined English literature led by figures like Alexander Pope and Samuel Johnson. Swift contributed to The Tatler, a popular periodical that shaped public discourse in London’s coffee-houses, the setting for the essay’s critique of trendy writing.

Linguistic Concerns: Swift was deeply invested in language reform, as seen in On Style and his later A Proposal for Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining the English Tongue (1712), where he suggested an English academy like the French Académie Française. His dislike of slang, abbreviations, and affected styles in On Style reflects his belief that clear language is essential for clear thought.

Satirical Persona: Using Isaac Bickerstaff, a well-known Tatler persona, Swift adopts a fictional correspondent’s voice in On Style to mock bad writing with irony, a technique consistent with his satirical works.

Personal Life and Later Years

Relationships: Swift never married but had close relationships with Esther Johnson (“Stella”), whom he met at Moor Park, and Esther Vanhomrigh (“Vanessa”). His correspondence with them reveals a complex personal life, though debates persist about the nature of these relationships.

Health and Decline: In his later years, Swift suffered from Ménière’s disease, causing vertigo and hearing loss, and possibly dementia. By 1742, he was declared mentally unfit and died on October 19, 1745, in Dublin.

Legacy: Swift left his fortune to found a hospital for the mentally ill (now St. Patrick’s Hospital, Dublin). His works remain influential for their satire, linguistic precision, and social commentary.

Word Meaning

| Tough Word | Meaning in English | Meaning in Hindi |

| Laid before | Presented or brought to attention. | प्रस्तुत किया, सामने रखा |

| Manifest | Clear or obvious to the eye or mind; evident. | स्पष्ट, प्रत्यक्ष |

| Overlooked | Failed to notice or consider. | अनदेखा किया, नजरअंदाज किया |

| Amend | To correct or improve. | सुधारना, ठीक करना |

| Affectation | Artificial behavior or speech to impress; pretense. | बनावटीपन, दिखावा |

| Epistle | A formal or literary letter. | पत्र, विशेष रूप से साहित्यिक पत्र |

| Wit | Cleverness or humor in expression. | बुद्धि, हास्य |

| Discernment | The ability to judge well; insight. | विवेक, समझ |

| Discourses | Written or spoken discussions; essays or speeches. | चर्चाएँ, लेख या भाषण |

| Treats of | Deals with or discusses (a subject). | चर्चा करता है, विषय को संभालता है |

| Correspondent | A person who writes a letter; here, the letter’s author. | पत्र लेखक, संवाददाता |

| Abuses | Wrong or improper uses; corrupt practices. | दुरुपयोग, गलत व्यवहार |

| Reformation | The act of improving or correcting. | सुधार, परिवर्तन |

| Province | Area of responsibility or expertise. | क्षेत्र, जिम्मेदारी |

| Conversant | Familiar or knowledgeable about. | परिचित, जानकार |

| Deplorable | Deserving strong condemnation; shockingly bad. | निंदनीय, दुखद |

| Ignorance | Lack of knowledge or awareness. | अज्ञान, अनभिज्ञता |

| Hath | Archaic third-person singular of “have” (has). | है (पुरातन, has का रूप) |

| Reigned | Dominated or prevailed. | शासन किया, प्रबल रहा |

| Depravity | Moral corruption; wickedness. | भ्रष्टता, नीचता |

| Handle | Deal with or write about (in context of sciences). | संभालना, लिखना (विशिष्ट विषयों में) |

| Divinity | Theology or religious studies. | धर्मशास्त्र, ईश्वरत्व |

| Physic | Medicine or healing arts (archaic). | चिकित्सा, औषधि |

| Traders | People engaged in a profession; here, writers. | व्यवसायी, यहाँ लेखक |

| Belles lettres | Literature valued for aesthetic qualities, like essays or poetry. | साहित्य, कला के लिए मूल्यवान लेखन |

| Done out of | Poorly or loosely translated (colloquial). | खराब अनुवाद, ढीला अनुवाद |

| Grub Street | A term for low-quality, hack writing or writers. | निम्न-स्तरीय लेखन, सस्ता साहित्य |

| Sheepskin | Leather used for bookbinding; here, cheap binding. | भेड़ की खाल, सस्ती किताब बाइंडिंग |

| Shilling | A former British coin, worth about 1/20 of a pound. | शिलिंग, पुरानी ब्रिटिश मुद्रा |

| Pedlars | Traveling vendors selling small goods. | फेरीवाले, छोटे सामान बेचने वाले |

| Handed | Passed or distributed (e.g., books being shared). | सौंपा गया, वितरित किया गया |

| Lapfuls | Large quantities, enough to fill a lap. | गोद भर, बड़ी मात्रा |

| Coffee-house | A social hub for discussion and reading in 18th-century London. | कॉफी-हाउस, सामाजिक चर्चा का केंद्र |

| Persons of quality | People of high social rank or status. | उच्च वर्ग के लोग, रईस |

| Westminster Hall | A historic building in London, part of the Palace of Westminster, used for courts. | वेस्टमिंस्टर हॉल, लंदन में ऐतिहासिक भवन |

| Court of Requests | A former English court for civil cases, often for the poor. | रिक्वेस्ट कोर्ट, सिविल मामलों का पुराना न्यायालय |

| Gilt | Covered with gold or gold-like material; luxurious. | सुनहरी परत, शानदार |

| Royal paper | High-quality paper, often used for expensive books. | शाही कागज, उच्च गुणवत्ता वाला कागज |

| Engage | Promise or undertake. | वचन देना, प्रतिबद्ध होना |

| Catalogue | A list or inventory. | सूची, सूचिपत्र |

| Compass | Scope or range; here, a time period. | दायरा, यहाँ समय अवधि |

| First hand | Directly from the source; original cost. | प्रत्यक्ष, मूल लागत |

| Common grammar | Basic, correct rules of language structure. | सामान्य व्याकरण, भाषा के सही नियम |

| Common sense | Basic reasoning or practical judgment. | सामान्य बुद्धि, व्यावहारिक समझ |

| Want of taste | Lack of good judgment in aesthetics or quality. | स्वाद की कमी, सौंदर्य की समझ की कमी |

| Timely remedy | A prompt solution to a problem. | समय पर उपाय, त्वरित समाधान |

| False refinements | Superficial or misguided improvements (sarcastic). | झूठे सुधार, सतही बदलाव (व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Foregoing | Previous or earlier. | पूर्ववर्ती, पहले का |

| Enlarge upon | Discuss in greater detail. | विस्तार से चर्चा करना |

| Animadversion | Criticism or censure; critical remarks. | आलोचना, निंदा |

| Crept | Moved slowly or secretly; here, changes sneaking into language. | धीरे-धीरे घुसना, चुपके से आना |

| Accomplished | Highly skilled or proficient (sarcastic here). | निपुण, कुशल (यहाँ व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Icou’dn’t | Slang abbreviation for “I couldn’t.” | मैं नहीं कर सका (संक्षिप्त) |

| Thôt | Slang abbreviation for “thought.” | सोचा (संक्षिप्त) |

| Ha’ | Slang abbreviation for “have.” | है (संक्षिप्त) |

| I’d | Contraction for “I would” or “I had.” | मैं करूँगा/मेरे पास था (संक्षिप्त) |

| H’ | Abbreviation for “have” (e.g., in “I’d h’ bôt”). | है (संक्षिप्त) |

| Bôt | Slang abbreviation for “bought.” | खरीदा (संक्षिप्त) |

| ’Um | Slang abbreviation for “them” (e.g., “bôt ‘um”). | उन्हें (संक्षिप्त) |

| Ha’n’t | Slang abbreviation for “have not.” | नहीं है (संक्षिप्त) |

| D’t | Slang abbreviation for “do it.” | करो (संक्षिप्त) |

| Pozz | Slang for “positive” or “for sure.” | निश्चित रूप से, पक्का |

| Gi’mself | Slang abbreviation for “give himself.” | अपने आप को देना (संक्षिप्त) |

| Plenipo’s | Short for plenipotentiaries, diplomats with full authority. | पूर्णाधिकारी राजनयिक |

| Bamboozl’ | To deceive or trick (slang). | धोखा देना, छलना |

| Agen | Archaic or slang for “again.” | फिर से (पुरातन/कठबोली) |

| Speculations | Theories or discussions about uncertain matters. | अटकलें, विचार-विमर्श |

| Jacks | Likely Jacobites or radicals (context-specific). | जैकबाइट्स, कट्टरपंथी (संदर्भ पर निर्भर) |

| Kidney | Type or kind (as in “of that kidney”). | प्रकार, श्रेणी |

| Uppish | Arrogant or conceited (slang). | घमंडी, अभिमानी |

| Upon’t | Slang contraction for “upon it.” | इस पर (संक्षिप्त) |

| Phizz’s | Faces (slang, from physiognomy). | चेहरे |

| Hazzard | Likely a proper name; contextually, a person (possibly fictional). | हैज़र्ड (संभवतः काल्पनिक व्यक्ति का नाम) |

| Hipps | Depression or melancholy (slang, from hypochondria). | उदासी, अवसाद |

| Hundr’d | Abbreviation for “hundred.” | सौ (संक्षिप्त) |

| Thô | Abbreviation for “though.” | यद्यपि (संक्षिप्त) |

| Promis’t | Archaic or slang abbreviation for “promised.” | वादा किया (पुरातन/संक्षिप्त) |

| Rep | Reputation (slang abbreviation). | प्रतिष्ठा |

| Leave off | To stop or abandon (e.g., a habit like gambling). | छोड़ देना, त्याग करना |

| ’Tis | Archaic contraction for “it is.” | यह है (पुरातन) |

| Apt | Likely or prone to (e.g., giving in to a weakness). | प्रवृत्त, संभावित (कमजोरी में पड़ने के लिए) |

| Lain | Archaic past participle of “lie” (to rest or hide, e.g., “lain incog.”). | छिपा हुआ (पुरातन, lie का रूप) |

| Incog. | Incognito, in disguise or hiding (abbreviation). | गुप्त, छिपा हुआ |

| Mobb | Mob, a disorderly crowd (slang spelling). | भीड़, अव्यवस्थित समूह |

| Bantr’d | Teased or mocked (slang, from banter). | मजाक किया, चिढ़ाया |

| Country put | A foolish or naive rural person (slang). | गँवार, देहाती मूर्ख |

| Shan’t | Contraction for “shall not.” | नहीं करूँगा (संक्षिप्त) |

| Admirable | Worthy of admiration (sarcastic here). | प्रशंसनीय (यहाँ व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Authority | Credibility or power (here, of the letter’s style). | प्रामाणिकता, शक्ति |

| Flower | A fine example or ornament (metaphorical, sarcastic). | फूल, उत्कृष्ट उदाहरण (यहाँ व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Sweetness | Charm or appeal (sarcastic). | मिठास, आकर्षण (यहाँ व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Want of wit | Lack of cleverness or intelligence. | बुद्धि की कमी |

| Breaks | Pauses or interruptions in writing (e.g., sentence ends). | रुकावट, विराम |

| Refinement | A change or improvement (often sarcastic). | सुधार, परिष्कार (अक्सर व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Elisions | Omissions of sounds or syllables (e.g., Icou’dn’t). | लोप, ध्वनि या अक्षर का हटाना |

| Obdurate | Stubbornly hard; here, harsh-sounding consonants. | कठोर, हठी |

| Intervene | Come between or separate. | बीच में आना, अलग करना |

| Syllable | A unit of pronunciation with one vowel sound. | अक्षर, स्वर ध्वनि की इकाई |

| Gothic strain | Crude style, like Northern European languages. | गोथिक शैली, असभ्य भाषा |

| Relapsing | Falling back into a worse state. | पुनः खराब स्थिति में जाना |

| Barbarity | Savage or uncivilized state. | जंगलीपन, असभ्यता |

| Monosyllables | Words with one syllable (e.g., mobb). | एकल अक्षर शब्द |

| Cram | Force or stuff tightly. | ठूँसना, जबरदस्ती भरना |

| Owl | A bird; here, used in an analogy for cutting words. | उल्लू (यहाँ शब्द कटौती के दृष्टांत में) |

| Mice | Small rodents; here, part of the owl analogy. | चूहे (यहाँ उल्लू के दृष्टांत का हिस्सा) |

| Bit off | Cut or removed by biting; here, part of the analogy. | काट लिया (यहाँ दृष्टांत का हिस्सा) |

| Maiming | Severely injuring or crippling. | विकृत करना, गंभीर चोट |

| Hitherto | Up to this time; so far. | अब तक, अभी तक |

| Plenipo | Short for plenipotentiary, a diplomat with full authority. | राजनयिक, पूर्णाधिकारी (संक्षिप्त) |

| Docked | Shortened or cut off. | काटा हुआ, छोटा किया |

| Inc. | Abbreviation for “incognito” (shortened form). | गुप्त (संक्षिप्त) |

| Plen | Abbreviation for “plenipotentiary” (shortened form). | राजनयिक (संक्षिप्त) |

| Impatient | Eager or restless for something (here, peace). | अधीर, बेचैन |

| Abundance | A large quantity; plenty. | बहुतायत, प्रचुरता |

| Polysyllables | Words with multiple syllables (e.g., speculations). | बहु-अक्षर शब्द |

| Campaigns | Periods of activity; here, metaphorically for word usage. | अभियान, यहाँ शब्द प्रयोग |

| Palisadoes | Defensive stakes or fortifications (war term). | रक्षात्मक खंभे, किलेबंदी |

| Circumvallation | A defensive wall or rampart (war term). | परिघेरा, रक्षात्मक दीवार |

| Battalions | Military units or large groups. | बटालियन, सैन्य टुकड़ी |

| Put to flight | Drive away or defeat. | भगाना, हार देना |

| Cut off | Remove or eliminate; here, metaphorically for words. | हटाना, काट देना (यहाँ शब्दों के लिए रूपक) |

| Rear | The back or last part (military metaphor). | पीछे, अंतिम भाग |

| Vogue | Fashion or popularity. | प्रचलन, फैशन |

| Possession | Ownership or dominance (here, of popularity). | कब्जा, प्रभुत्व (यहाँ लोकप्रियता) |

| Utmost | Greatest effort or extent. | अधिकतम, पूरी कोशिश |

| Borne down | Overwhelmed or defeated by numbers or force. | दब जाना, हार जाना |

| Scattered | Spread or dispersed randomly. | बिखरा हुआ, फैला हुआ |

| Worn to rags | Overused until worthless, like tattered cloth. | चिथड़े हो जाना, अत्यधिक उपयोग |

| Servile | Overly imitative or submissive. | दासवत, अंधानुकरण करने वाला |

| Imitators | People who copy others. | नकल करने वाले, अनुकरणकर्ता |

| Disturb | Highlight or point out (archaic sense). | उजागर करना, इंगित करना (पुराना अर्थ) |

| Censor | An official who suppresses unacceptable content; here, a critic. | सेंसर, आलोचक (यहाँ) |

| Index Expurgatorius | A list of banned items, here for words (satirical). | निषिद्ध सूची, यहाँ शब्दों के लिए (व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Expunge | Erase or remove completely. | मिटाना, हटाना |

| Offensive | Causing displeasure or harm. | अपमानजनक, हानिकारक |

| Condemn | Strongly criticize or denounce. | निंदा करना, भर्त्सना करना |

| Barbarous | Savage, crude, or uncivilized. | जंगली, असभ्य |

| Mutilations | Severe damage; here, to words by chopping syllables. | विकृति, शब्दों की काट-छाँट |

| Pretence | Excuse or false reason. | बहाना, झूठा कारण |

| Noble standard | High or admirable measure (sarcastic). | उच्च मानक (यहाँ व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Caprice | Sudden, impulsive change or whim. | सनक, आवेग |

| Coxcomb | A vain or conceited fool. | घमंडी मूर्ख, फॉप |

| Content | Satisfied or pleased. | संतुष्ट, प्रसन्न |

| Sparing | Restrained or limited in use. | संयमित, कम उपयोग |

| Liberal | Generous or abundant; here, using full syllables. | उदार, यहाँ पूर्ण अक्षर |

| Bestow | Give or present (here, advice). | प्रदान करना, देना (यहाँ सलाह) |

| Fraught | Filled or loaded with (often negative). | भरा हुआ, लदा हुआ |

| Town politeness | Fashionable urban manners (sarcastic). | शहरी शिष्टता (व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Prayer-books | Books containing religious prayers, like the Book of Common Prayer. | प्रार्थना पुस्तकें, धार्मिक प्रार्थनाएँ |

| Absolution | Formal forgiveness of sins in church. | पापमोचन, क्षमा |

| Pardons | Acts of forgiveness; here, part of the Absolution prayer. | क्षमा, यहाँ पापमोचन प्रार्थना का हिस्सा |

| Absolves | Grants forgiveness (in a religious context). | क्षमा देता है (धार्मिक संदर्भ में) |

| ’Endue ‘um | Slang abbreviation for “endue them” (to endow or provide). | उन्हें प्रदान करें (संक्षिप्त) |

| Enrich ‘um | Slang abbreviation for “enrich them.” | उन्हें समृद्ध करें (संक्षिप्त) |

| Prosper ‘um | Slang abbreviation for “prosper them.” | उन्हें समृद्ध करें (संक्षिप्त) |

| Bring ‘um | Slang abbreviation for “bring them.” | उन्हें लाएँ (संक्षिप्त) |

| Sermons | Religious speeches or lectures delivered in church. | उपदेश, चर्च में धार्मिक भाषण |

| Modern terms of art | Contemporary jargon or specialized terms (sarcastic). | आधुनिक शब्दजाल (यहाँ व्यंग्यात्मक) |

| Sham | Something fake or fraudulent (slang). | धोखा, नकली |

| Bubble | A scam or fraudulent scheme (slang). | घोटाला, धोखाधड़ी |

| Bully | A person who intimidates others (slang). | धमकाने वाला, गुंडा |

| Cutting | Cheating or swindling (slang). | धोखा देना, ठगना |

| Shuffling | Deceiving or evading (slang). | चकमा देना, टालमटोल |

| Palming | Sleight of hand or deception (slang). | हथेली में छिपाना, छल |

| Stamp | Type or kind; here, similar style (e.g., “of the like stamp”). | प्रकार, यहाँ समान शैली |

| Pulpit | A platform for preaching in a church. | मंच, चर्च में उपदेश का स्थान |

| Sophisters | People who argue cleverly but deceitfully; here, young preachers. | चतुर वक्ता, यहाँ युवा उपदेशक (नकारात्मक) |

| Dreadful | Terrible or causing fear (here, of being called pedantic). | भयानक, डरावना (यहाँ विद्वत्तापूर्ण कहलाने का) |

| Imputation | Accusation or suggestion (here, of pedantry). | इल्ज़ाम, आरोप |

| Pedantry | Excessive focus on academic details or formality. | पांडित्य, अनावश्यक विद्वता |

| Poring | Studying intently or laboriously. | गहराई से पढ़ना, तल्लीन होना |

| Unfashionable | Outdated or not in style. | अप्रचलित, पुराना |

| Instrument | A means or tool for achieving something. | साधन, उपकरण |

| Ornament | Decoration or enhancement. | अलंकरण, सजावट |

| Politer ages | More refined historical periods (e.g., classical or Elizabethan eras). | अधिक परिष्कृत युग, सुसंस्कृत काल |

| Simplex munditiis | Latin phrase meaning “simple elegance.” | साधारण शालीनता (लैटिन) |

| Affected | Artificial or pretentious; done to impress. | बनावटी, दिखावटी |

| Perishing | Dying out or disappearing. | नष्ट होना, गायब होना |

| Hooker | Richard Hooker, an Elizabethan theologian (proper name). | रिचर्ड हूकर (एलिजाबेथन धर्मशास्त्री का नाम) |

| Country clergyman | A priest serving in a rural area (here, referring to Hooker). | ग्रामीण पादरी (यहाँ हूकर को संदर्भित) |

| Parsons the Jesuit | Robert Parsons, a Jesuit priest (proper name). | रॉबर्ट पार्सन्स, जेसुइट पादरी (नाम) |

| Reign | Period of rule; here, Queen Elizabeth’s era. | शासन, यहाँ क्वीन एलिजाबेथ का युग |

| Allowances | Adjustments or concessions (e.g., for outdated style). | छूट, समायोजन |

| Intelligible | Understandable or clear. | समझने योग्य, स्पष्ट |

| Men of the court | Courtiers or people associated with the royal court. | दरबारी, शाही दरबार से जुड़े लोग |

| Ridiculous | Laughably absurd or silly. | हास्यास्पद, मूर्खतापूर्ण |

| Remedies | Solutions or cures for problems. | उपाय, समाधान |

| Taken up | Occupied or used (e.g., space or time). | उपयोग किया, कब्जा किया |

| Office | Duty or role. | कर्तव्य, भूमिका |

| Represent | Describe or point out. | प्रस्तुत करना, इंगित करना |

| Redress | Correct or remedy (a wrong). | सुधारना, ठीक करना |

| Respect | Esteem or regard (formal closing). | सम्मान, आदर |

| Your, &c. | Standard letter closing, implying “Your servant” or similar (abbreviated). | आपका, आदि (औपचारिक पत्र समापन) |

On Style by Jonathan Swift Questions and Answers

Very Short Answer Questions

Who wrote On Style?

Jonathan Swift.

Under what pseudonym was On Style published?

Isaac Bickerstaff.

In which periodical did On Style appear?

The Tatler.

What is the publication date of On Style in The Tatler?

September 23–26, 1710.

What is the main format of On Style?

A letter.

Who is the letter in On Style addressed to?

Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq.

What are the three main problems criticized in the essay?

Ignorance, bad taste, and language corruption.

What type of writers does the essay focus on?

History, politics, and belles lettres writers.

What is “Grub Street” in the essay?

A term for low-quality hack writing.

What is the satirical letter in the essay meant to show?

Bad, trendy writing style.

Name one slang term from the satirical letter.

Bamboozle.

What is an example of an abbreviation in the satirical letter?

Icou’dn’t.

What does the essay blame for the “corruption” of English?

False refinements.

What solution does the correspondent suggest for bad words?

An Index Expurgatorius.

What group does Swift criticize for using slang in sermons?

Young clergy.

What writing style does Swift advocate for?

Simplicity.

Name an Elizabethan writer Swift praises for clear style.

Richard Hooker.

Name a later writer Swift criticizes for obscure style.

Sir H. Wootton.

What Latin phrase does Swift use to describe elegant simplicity?

Simplex munditiis.

What does the correspondent claim is Bickerstaff’s role?

To redress the abuses.

Short Answer Questions

Who is Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq.?

“Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq.” refers to a fictional persona created by Jonathan Swift, used as the pseudonymous author of The Tatler, a periodical where Swift’s essay On Style appeared in 1710. The title “Esq.” (short for Esquire) was a formal honorific in 18th-century England, typically used for gentlemen of respectable social standing, often implying wealth or education, but not nobility.

What is the main purpose of Swift’s On Style?

Swift aims to criticize the decline of English writing due to ignorance, bad taste, and corrupted style. He uses satire to mock trendy slang, abbreviations, and affected politeness, advocating for clear, simple language. The essay, presented as a letter to Isaac Bickerstaff, exposes these flaws through a mock letter and urges reform. Published in The Tatler, it reflects Swift’s broader concern for linguistic clarity.

How does Swift use the satirical letter in the essay to make his point?

Swift includes a fake letter filled with slang (bamboozle, mobb), abbreviations (Icou’dn’t, thôt), and choppy sentences to parody the trendy, “polite” writing style of his time. By exaggerating these flaws, he shows how such language is unclear and shallow. The correspondent sarcastically calls it an “admirable pattern” to highlight its absurdity. This satire makes Swift’s critique vivid and engaging.

What are the three main writing flaws Swift identifies in the essay?

Swift, through the correspondent, identifies ignorance (lack of knowledge), want of taste (poor aesthetic judgment), and the continual corruption of the English tongue as the main flaws. Ignorance leads to poorly written books, bad taste elevates low-quality works, and language corruption stems from trendy slang and abbreviations. These issues, he argues, have worsened over the past 20 years, threatening English’s clarity.

Why does Swift criticize young clergy in On Style?

Swift mocks young clergy for adopting trendy slang like sham and banter in sermons and altering prayer-book phrases (e.g., “endue ‘um” instead of “endue them”). He sees this as a shallow attempt to seem modern and avoid pedantry. Influenced by urban “politeness,” they prioritize fashion over clarity. Swift finds this misuse of language in sacred contexts particularly egregious.

What role does Swift assign to Isaac Bickerstaff in the essay?

Swift, as the fictional correspondent, urges Bickerstaff to act as a censor to fix bad writing trends. He suggests Bickerstaff use persuasion or a satirical Index Expurgatorius to ban senseless words and phrases. This role is ironic, as Bickerstaff is Swift’s pseudonym, implying Swift himself is calling for reform. It emphasizes the need for authority to restore linguistic standards.

How does Swift contrast older and newer writers in the essay?

Swift praises Elizabethan writers like Richard Hooker and Robert Parsons for their clear, timeless style, still understandable today. He contrasts them with later writers like Sir H. Wootton and Sir Robert Naunton, whose courtly, trendy phrases are now obscure or ridiculous. This comparison supports his argument for simplicity over fashionable affectation. It shows how fleeting trends harm lasting communication.

What is the significance of the Index Expurgatorius in Swift’s argument?

The Index Expurgatorius, a proposed yearly list to ban offensive words, is a satirical solution to purge slang and abbreviations. It mimics Catholic lists of forbidden books, adding humor to Swift’s critique. While not a serious proposal, it underscores his desire for linguistic standards. It reflects his frustration with the unchecked spread of bad writing habits.

How does the essay reflect the historical context of early 18th-century London?

On Style captures the growing print culture and coffee-house debates of Augustan London, where The Tatler was widely read. Swift references places like Westminster Hall and the War of the Spanish Succession, tying the essay to contemporary politics and society. The rise of hack writers (Grub Street) and trendy urban speech fuels his critique. It shows a society grappling with rapid cultural change.

What does Swift mean by advocating for “simplicity” in writing?

Swift calls for a clear, elegant writing style, free of trendy slang or artificial flourishes, as the best way to communicate. He cites the Latin phrase simplex munditiis (simple elegance) to emphasize this ideal, seen in past writers like Hooker. Simplicity ensures clarity and timelessness, unlike fleeting, affected styles. It’s a call to prioritize substance over fashion.

Why does Swift use satire in On Style instead of a straightforward critique?

Swift uses satire, like the exaggerated mock letter and ironic tone, to make his critique of bad writing engaging and memorable. By mocking slang and proposing absurd solutions like the Index Expurgatorius, he exposes the absurdity of trendy styles. Satire entertains Tatler’s readers while subtly urging reform. It aligns with Swift’s style, seen in works like Gulliver’s Travels.

Essay Type Questions

Write Long Note on Jonathan Swift as Essayist.

Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), an Anglo-Irish satirist, poet, and clergyman, is widely regarded as one of the most incisive and influential essayists in the English language. Best known for his novel Gulliver’s Travels (1726), Swift’s essays showcase his mastery of satire, irony, and lucid prose, addressing societal, political, and cultural issues with unparalleled wit and moral fervor. As an essayist, Swift combined intellectual rigor with accessibility, using the essay form to critique human folly, advocate reform, and shape public discourse in the Augustan Age. This note explores Swift’s contributions as an essayist, focusing on his style, themes, key works, historical context, and lasting impact, with reference to his essay On Style (1708) and other significant essays.

Swift’s Background and Literary Context

Born in Dublin to English parents, Swift’s life was marked by financial hardship, political engagement, and a complex identity as both an Englishman and an Irish patriot. Educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and Oxford, he served as a secretary to Sir William Temple, which exposed him to literary and political circles. Ordained as an Anglican priest in 1695, Swift became Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, in 1713, but his literary career flourished through his satirical writings.

The Augustan Age (late 17th to early 18th century), characterized by refined prose and neoclassical ideals, provided a fertile context for Swift’s essays. Alongside contemporaries like Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, Swift contributed to periodicals like The Tatler and The Examiner, using the essay to engage a growing middle-class readership in London’s coffee-house culture.

Swift’s essays emerged during a time of rapid print culture expansion, political upheaval (e.g., the War of the Spanish Succession, 1701–1714), and linguistic evolution. His conservative views on language and society, rooted in admiration for classical clarity and Elizabethan writers like Richard Hooker, shaped his critiques of contemporary trends.

Characteristics of Swift’s Essayistic Style

Swift’s essays are defined by a distinctive style that blends satire, irony, and clarity, making complex ideas accessible and engaging:

Satire and Irony: Swift’s essays use biting satire to expose human flaws. In On Style, he employs a mock letter filled with slang (bamboozle, mobb) to parody trendy writing, ironically calling it an “admirable pattern.” His irony often masks serious critiques, as in A Modest Proposal (1729), where he “proposes” eating Irish children to highlight British neglect.

Lucid Prose: Despite his satirical flourishes, Swift’s prose is clear and precise, reflecting his advocacy for simplicity (simplex munditiis). His sentences are conversational yet structured, appealing to both educated and general readers.