Am I Blue?

Summary

Alice Walker’s short story “Am I Blue?” was first published in 1986 in Ms. Magazine. The essay, written in the style of a short story, reflects on Walker’s relationship with a horse named Blue and explores themes of empathy, suffering, and disconnection between humans and animals.

In 1988, “Am I Blue?” was included in Walker’s essay collection Living by the Word: Selected Writings 1973-1987, published by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. The story has since been anthologized in various collections and continues to be studied for its poignant commentary on human-animal relationships. The story uses the emotional journey of a horse named Blue to critique societal ignorance of animal sentience and draw parallels to human injustices like slavery and patriarchy.

The title, Am I Blue?, echoes the 1929 jazz standard popularized by Billie Holiday, with the line “Ain’t these tears in my eyes tellin’ you?” (slightly misquoted in essay’s opening as “Ain’t these tears in these eyes tellin’ you?”). The song’s lament of loneliness and betrayal resonates with Blue’s experience and the essay’s broader themes. Walker uses this to underscore the universal language of suffering, ignored by those who choose not to see.

In Alice Walker’s short story “Am I Blue”, the narrator and their partner rent a small countryside house overlooking a vast meadow stretching toward distant mountains. From their window, they observe a large white horse named Blue, confined to a five-acre fenced field owned by nearby neighbors. Blue belongs to someone from another town and is occasionally ridden by neighborhood children, but mostly, he wanders alone, grazing and flipping his mane.

As the seasons change and the meadow grasses dry up, the narrator notices Blue’s increasing boredom and loneliness. They begin feeding him apples from a tree near the fence, which Blue eagerly accepts—whinnying and stamping for more. The narrator is captivated by Blue’s expressive eyes and powerful presence, recalling their childhood experience with horses and realizing how clearly animals communicate emotions, something adults often forget.

The story takes a hopeful turn when a brown horse arrives in Blue’s field. Initially wary, Blue soon befriends the newcomer, and together they display a renewed sense of freedom and vitality. The narrator calls this Blue’s “inalienable horseness,” a proud independence that brings peace and connection to the horses—and to the narrator, who feeds them both.

However, this happiness is short-lived. The brown horse disappears after becoming pregnant, taken away by her owner. Blue’s behavior becomes frantic and sorrowful; his eyes reveal not just grief but a deep disgust with human cruelty. The narrator draws powerful parallels between Blue’s suffering and historical human injustices like slavery and cultural oppression.

Throughout “Am I Blue by Alice Walker,” the narrator reflects on society’s disregard for animal feelings, equating it with the dismissal of oppressed groups. Walker critiques how animals are commodified and reduced to symbols—like “happy cows” on milk cartons—while their real pain is ignored. The narrator’s final act of spitting out a steak during a conversation about justice poignantly symbolizes a breaking point, a call to recognize the interconnectedness of suffering across species.

In essence, “Am I Blue by Alice Walker” is a deeply moving narrative that uses the story of a lonely horse to explore themes of empathy, loss, and social injustice. Through Blue’s eyes, Walker urges readers to acknowledge the sentience of animals and reconsider the ways humans perpetuate cruelty—whether through exploitation, indifference, or silence.

Essay

Ain’t these tears in these eyes tellin’ you?’

For about three years my companion and I rented a small house in the country that stood on the edge of a large meadow that appeared to run from the end of our deck straight into the mountains. The mountains, however, were quite far away, and between us and them there was, in fact, a town. It was one of the many pleasant aspects of the house that you never really were aware of this.

It was a house of many windows, low, wide, nearly floor to ceiling in the living room, which faced the meadow, and it was from one of these that I first saw our closest neighbor, a large white horse, cropping grass, flipping its mane, and ambling about—not over the entire meadow, which stretched well out of sight of the house, but over the five or so fenced-in acres that were next to the twenty-odd that we had rented. I soon learned that the horse, whose name was Blue, belonged to a man who lived in another town, but was boarded by our neighbours next door. Occasionally, one of the children, usually a stocky teenager, but sometimes a much younger girl or boy, could be seen riding Blue. They would appear in the meadow, climb up on his back, ride furiously for ten or fifteen minutes, then get off, slap Blue on the flanks, and not be seen again for a month or more.

There were many apple trees in our yard, and one by the fence that Blue could almost reach. We were soon in the habit of feeding him apples, which he relished, especially because by the middle of summer the meadow grasses—so green and succulent since January—had dried out from lack of rain, and Blue stumbled about munching the dried stalks half-heartedly. Sometimes he would stand very still just by the apple tree, and when one of us came out he would whinny, snort loudly, or stamp the ground. This meant, of course: I want an apple.

It was quite wonderful to pick a few apples, or collect those that had fallen to the ground overnight, and patiently hold them, one by one, up to his large, toothy mouth. I remained as thrilled as a child by his flexible dark lips, huge, cubelike teeth that crunched the apples, core and all, with such finality, and his high, broad-breasted enormity; beside which, I felt small indeed. When I was a child, I used to ride horses, and was especially friendly with one named Nan until the day I was riding and my brother deliberately spooked her and I was thrown, head first, against the trunk of a tree. When I came to, I was in bed and my mother was bending worriedly over me; we silently agreed that perhaps horseback riding was not the safest sport for me. Since then I have walked, and prefer walking to horseback riding—but I had forgotten the depth of feeling one could see in horses’ eyes.

I was therefore unprepared for the expression in Blue’s. Blue was lonely. Blue was horribly lonely and bored. I was not shocked that this should be the case; five acres to tramp by yourself, endlessly, even in the most beautiful of meadows—and his was—cannot provide many interesting events, and once rainy season turned to dry that was about it. No, I was shocked that I had forgotten that human animals and nonhuman animals can communicate quite well; if we are brought up around animals as children we take this for granted. By the time we are adults we no longer remember. However, the animals have not changed. They are in fact completed creations (at least they seem to be, so much more than we) who are not likely to change; it is their nature to express themselves. What else are they going to express? And they do. And, generally speaking, they are ignored.

After giving Blue the apples, I would wander back to the house, aware that he was observing me. Were more apples not forthcoming then? Was that to be his sole entertainment for the day? My partner’s small son had decided he wanted to learn how to piece a quilt; we worked in silence on our respective squares as I thought…

Well, about slavery: about white children, who were raised by black people, who knew their first all-accepting love from black women, and then, when they were twelve or so, were told they must ‘forget’ the deep levels of communication between themselves and ‘mammy’ that they knew. Later they would be able to relate quite calmly, ‘My old mammy was sold to another good family.’ ‘My old mammy was — —.’ Fill in the blank. Many more years later a white woman would say: ‘I can’t understand these Negroes, these blacks. What do they want? They’re so different from us.’

And about the Indians, considered to be ‘like animals’ by the ‘settlers’ (a very benign euphemism for what they actually were), who did not understand their description as a compliment.

And about the thousands of American men who marry Japanese, Korean, Filipina, and other non-English-speaking women and of how happy they report they are, ‘blissfully’, until their brides learn to speak English, at which point the marriages tend to fall apart. What then did the men see, when they looked into the eyes of the women they married, before they could speak English? Apparently only their own reflections.

I thought of society’s impatience with the young. ‘Why are they playing the music so loud?’ Perhaps the children have listened to much of the music of oppressed people their parents danced to before they were born, with its passionate but soft cries for acceptance and love, and they have wondered why their parents failed to hear.

I do not know how long Blue had inhabited his five beautiful, boring acres before we moved into our house; a year after we had arrived—and had also travelled to other valleys, other cities, other worlds—he was still there.

But then, in our second year at the house, something happened in Blue’s life. One morning, looking out the window at the fog that lay like a ribbon over the meadow, I saw another horse, a brown one, at the other end of Blue’s field. Blue appeared to be afraid of it, and for several days made no attempt to go near. We went away for a week. When we returned, Blue had decided to make friends and the two horses ambled or galloped along together, and Blue did not come nearly as often to the fence underneath the apple tree.

When he did, bringing his new friend with him, there was a different look in his eyes. A look of independence, of self-possession, of inalienable horseness. His friend eventually became pregnant. For months and months there was, it seemed to me, a mutual feeling between me and the horses of justice, of peace. I fed apples to them both. The look in Blue’s eyes was one of unabashed ‘this is fitness’.

It did not, however, last forever. One day, after a visit to the city, I went out to give Blue some apples. He stood waiting, or so I thought, though not beneath the tree. When I shook the tree and jumped back from the shower of apples, he made no move. I carried some over to him. He managed to half-crunch one. The rest he let fall to the ground. I dreaded looking into his eyes—because I had of course noticed that Brown, his partner, had gone—but I did look. If I had been born into slavery, and my partner had been sold or killed, my eyes would have looked like that. The children next door explained that Blue’s partner had been ‘put with him’ (the same expression that old people used, I had noticed, when speaking of an ancestor during slavery who had been impregnated by her owner) so that they could mate and she conceive. Since that was accomplished, she had been taken back by her owner, who lived somewhere else.

Will she be back? I asked.

They didn’t know.

Blue was ‘like a crazed person. Blue was, to me, a crazed person. He galloped furiously, as if he were being ridden, around and around his five beautiful acres. He whinnied until he couldn’t. He tore at the ground with his hooves. He butted himself against his single shade tree. He looked always and always towards the road down which his partner had gone. And then, occasionally, when he came up for apples, or I took apples to him, he looked at me. It was a look so piercing, so full of grief, a look so human, I almost laughed (I felt too sad to cry) to think there are people who do not know what animals suffer. People like me who have forgotten, and daily forget, all that animals try to tell us. ‘Everything you do to us will happen to you; we are your teachers, as you are ours. We are one lesson’ is essentially it, I think. There are those who never once have even considered animals’ rights: those who have been taught that animals actually want to be used and abused by us, as small children ‘love’ to be frightened, or women ‘love’ to be mutilated and raped… They are the great-grandchildren of those who honestly thought, because someone taught them this: ‘Women can’t think,’ and ‘niggers can’t faint.’ But most disturbing of all, in Blue’s large brown eyes was a new look, more painful than the look of despair: the look of disgust with human beings, with life; the look of hatred. And it was odd what the look of hatred did. It gave him, for the first time, the look of a beast. And what that meant was that he had put up a barrier within to protect himself from further violence: all the apples in the world wouldn’t change that fact.

And so Blue remained, a beautiful part of our landscape, very peaceful to look at from the window, white against the grass. Once a friend came to visit and said, looking out on the soothing view: ‘And it would have to be a white horse; the very image of freedom.’ And I thought, yes, the animals are forced to become for us merely ‘images’ of what they once so beautifully expressed. And we are used to drinking milk from containers showing ‘contented’ cows, whose real lives we want to hear nothing about, eating eggs and drumsticks from ‘happy’ hens, and munching hamburgers advertised by bulls of integrity who seem to command their fate.

As we talked of freedom and justice one day for all, we sat down to steaks. I am eating misery, I thought, as I took the first bite. And spit it out.

Am I Blue by Alice Walker Analysis

Ain’t these tears in these eyes tellin’ you?’

The line “Ain’t these tears in these eyes tellin’ you?” is a quote from the jazz song “Am I Blue?” and serves as the opening of Alice Walker’s essay. In simple terms, it’s like the narrator is pointing to the sadness in the horse Blue’s eyes, asking the reader, “Can’t you see how much pain he’s in?” It sets the emotional tone for the story, suggesting that Blue’s feelings are obvious if you just look closely. The line connects to the story’s main idea: animals, like humans, feel deep emotions, and their suffering deserves our attention. By starting with this, Walker grabs the reader’s heart, urging them to notice and care about Blue’s loneliness and grief, which unfold in the essay.

For about three years my companion and I rented a small house in the country that stood on the edge of a large meadow that appeared to run from the end of our deck straight into the mountains. The mountains, however, were quite far away, and between us and them there was, in fact, a town. It was one of the many pleasant aspects of the house that you never really were aware of this.

In this paragraph, Alice Walker describes the setting of her story “Am I Blue?” in a simple and vivid way. She explains that for about three years, she and her partner lived in a small house in a rural area. The house was located next to a large meadow, which looked like it stretched all the way from their deck to the distant mountains. However, the mountains were actually far away, and there was a town between the house and the mountains. One of the nice things about the house was that you didn’t notice the town, so it felt like you were surrounded by nature. In easy terms, Walker is painting a peaceful picture of a countryside home with a beautiful view that makes you feel closer to nature than you really are, setting a calm and reflective mood for the story.

It was a house of many windows, low, wide, nearly floor to ceiling in the living room, which faced the meadow, and it was from one of these that I first saw our closest neighbor, a large white horse, cropping grass, flipping its mane, and ambling about—not over the entire meadow, which stretched well out of sight of the house, but over the five or so fenced-in acres that were next to the twenty-odd that we had rented. I soon learned that the horse, whose name was Blue, belonged to a man who lived in another town, but was boarded by our neighbours next door. Occasionally, one of the children, usually a stocky teenager, but sometimes a much younger girl or boy, could be seen riding Blue. They would appear in the meadow, climb up on his back, ride furiously for ten or fifteen minutes, then get off, slap Blue on the flanks, and not be seen again for a month or more.

In this paragraph, Alice Walker continues to describe the setting and introduces Blue, the horse, in her story “Am I Blue?” in a clear and relatable way. She explains that the house they rented had lots of big, low windows, especially in the living room, which looked out onto the meadow. Through one of these windows, she first saw a large white horse named Blue, who was eating grass, tossing his mane, and wandering around. Blue didn’t roam the whole meadow, which was huge and stretched far beyond what they could see from the house, but stayed in a smaller, fenced-in area of about five acres next to the roughly twenty acres they rented. Walker learned that Blue belonged to a man from another town but was taken care of by their neighbors next door. Sometimes, kids from the neighborhood—usually a sturdy teenager, but occasionally a younger boy or girl—would show up, ride Blue fast for ten or fifteen minutes, pat him, and then disappear for weeks or even a month. In simple terms, Walker is setting the scene by describing the house’s view, introducing Blue as a lonely horse stuck in a small space, and showing how people, like the kids, interact with him briefly and without much care, hinting at his isolation.

There were many apple trees in our yard, and one by the fence that Blue could almost reach. We were soon in the habit of feeding him apples, which he relished, especially because by the middle of summer the meadow grasses—so green and succulent since January—had dried out from lack of rain, and Blue stumbled about munching the dried stalks half-heartedly. Sometimes he would stand very still just by the apple tree, and when one of us came out he would whinny, snort loudly, or stamp the ground. This meant, of course: I want an apple.

In this paragraph, Alice Walker describes a small but meaningful connection between the narrator and Blue, the horse, in her story “Am I Blue?” in a simple and vivid way. She explains that their yard had many apple trees, including one close to the fence near Blue’s field, just out of his reach. The narrator and their partner got into the habit of feeding Blue apples, which he loved, especially in the middle of summer when the meadow’s lush green grass, vibrant since January, had dried up due to no rain. Without fresh grass, Blue wandered around, nibbling on dry stalks with little enthusiasm. Sometimes, Blue would stand quietly by the apple tree, and when someone came outside, he’d make noises—whinnying, snorting loudly, or stamping his foot—to clearly say, “I want an apple!” In easy terms, Walker shows how Blue’s world is tough with dry grass and loneliness, but the apples become a small joy and a way for the narrator to bond with him, highlighting his eagerness and personality.

It was quite wonderful to pick a few apples, or collect those that had fallen to the ground overnight, and patiently hold them, one by one, up to his large, toothy mouth. I remained as thrilled as a child by his flexible dark lips, huge, cubelike teeth that crunched the apples, core and all, with such finality, and his high, broad-breasted enormity; beside which, I felt small indeed. When I was a child, I used to ride horses, and was especially friendly with one named Nan until the day I was riding and my brother deliberately spooked her and I was thrown, head first, against the trunk of a tree. When I came to, I was in bed and my mother was bending worriedly over me; we silently agreed that perhaps horseback riding was not the safest sport for me. Since then I have walked, and prefer walking to horseback riding—but I had forgotten the depth of feeling one could see in horses’ eyes.

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator describes the joy of interacting with Blue, the horse, and shares a personal memory that deepens their connection to him.

The narrator finds it delightful to pick apples from the tree or gather ones that fell to the ground overnight and feed them to Blue one at a time. They hold each apple up to Blue’s big, toothy mouth and are amazed, like a excited child, by how he eats them. Blue’s dark, flexible lips move, and his large, block-like teeth crunch the apples—core and all—with a strong, final bite. His huge size, with a tall, broad chest, makes the narrator feel small in comparison. This moment brings back memories of the narrator’s childhood when they used to ride horses and were especially close to one named Nan. But one day, while riding Nan, their brother scared the horse on purpose, causing the narrator to fall and hit their head on a tree trunk. When they woke up, they were in bed with their worried mother looking over them. Without saying much, they both agreed that horseback riding might be too dangerous for the narrator. Since then, they’ve preferred walking over riding horses and had forgotten how much emotion horses show in their eyes until seeing Blue.

In simple terms, this paragraph shows the narrator’s happiness in feeding Blue apples and marveling at his strength and size. It also reveals a past experience with horses that ended badly, explaining why the narrator stopped riding but is now rediscovering the deep feelings horses express, setting the stage for their growing bond with Blue.

I was therefore unprepared for the expression in Blue’s. Blue was lonely. Blue was horribly lonely and bored. I was not shocked that this should be the case; five acres to tramp by yourself, endlessly, even in the most beautiful of meadows—and his was—cannot provide many interesting events, and once rainy season turned to dry that was about it. No, I was shocked that I had forgotten that human animals and nonhuman animals can communicate quite well; if we are brought up around animals as children we take this for granted. By the time we are adults we no longer remember. However, the animals have not changed. They are in fact completed creations (at least they seem to be, so much more than we) who are not likely to change; it is their nature to express themselves. What else are they going to express? And they do. And, generally speaking, they are ignored.

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator reflects on the surprising depth of Blue’s emotions and their own realization about the connection between humans and animals.

The narrator was caught off guard by the look in Blue’s eyes, which showed that he was incredibly lonely and bored. They weren’t surprised that Blue felt this way, since being stuck alone in a five-acre field, even a beautiful one like his, wouldn’t offer much excitement. Once the rainy season ended and the grass dried up, there was even less for Blue to do. What shocked the narrator wasn’t Blue’s loneliness but their own realization that they’d forgotten something important: humans and animals can understand each other quite well. When we grow up around animals as kids, we naturally notice their feelings, like it’s no big deal. But as adults, we often forget this ability. The narrator points out that animals, unlike humans, haven’t changed. They seem like “completed creations,” meaning they’re fully themselves, always expressing their true emotions openly because that’s just who they are. Animals don’t hide their feelings, but most people ignore what they’re trying to say.

In simple terms, this paragraph shows the narrator being struck by how lonely Blue is and realizing they’d forgotten how clearly animals show their emotions. It’s a wake-up call that animals are honest and expressive, but humans often overlook them, setting up the story’s focus on empathy and connection.

After giving Blue the apples, I would wander back to the house, aware that he was observing me. Were more apples not forthcoming then? Was that to be his sole entertainment for the day? My partner’s small son had decided he wanted to learn how to piece a quilt; we worked in silence on our respective squares as I thought…

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator reflects on their interaction with Blue, the horse, and begins to ponder deeper thoughts.

After feeding Blue apples, the narrator walks back to the house, feeling Blue’s eyes on them. They wonder if Blue is hoping for more apples and if that brief moment of getting apples is the only excitement he’ll have all day. This thought highlights Blue’s lonely life, stuck in his small field with little to do. Meanwhile, inside the house, the narrator and their partner’s young son are quietly working on a quilting project, each focusing on their own piece of the quilt. As they sew in silence, the narrator’s mind starts to wander, setting the stage for deeper reflections that come later in the story.

In simple terms, this paragraph shows the narrator feeling a mix of connection and sadness after feeding Blue, noticing his longing for more attention. It also paints a calm, everyday scene at home with the quilting, while hinting that the narrator is starting to think about bigger ideas, like Blue’s loneliness and what it means, which ties into the story’s themes of empathy and awareness.

Well, about slavery: about white children, who were raised by black people, who knew their first all-accepting love from black women, and then, when they were twelve or so, were told they must ‘forget’ the deep levels of communication between themselves and ‘mammy’ that they knew. Later they would be able to relate quite calmly, ‘My old mammy was sold to another good family.’ ‘My old mammy was — —.’ Fill in the blank. Many more years later a white woman would say: ‘I can’t understand these Negroes, these blacks. What do they want? They’re so different from us.’

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator reflects on the painful history of slavery in America, connecting it to the story’s themes of emotional disconnection and loss.

The narrator thinks about how, during slavery, white children were often raised by enslaved Black women, sometimes called “mammy,” who cared for them with deep, unconditional love. These children felt a strong, genuine bond with these women, who were like family to them in their early years. But around age twelve, they were taught to “forget” this close connection because society enforced strict racial divisions. They were told that Black people were different and inferior, breaking the emotional tie they had known. As adults, these same children could speak casually about their “mammy” being sold to another family, as if it was no big deal, or leave her fate unsaid, like “My old mammy was…” without caring what happened to her. Years later, a white woman might say she doesn’t understand Black people, claiming they’re too different and questioning what they want, completely unaware of the history of love and loss that shaped these divides.

In simple terms, this paragraph shows how slavery forced people to cut off deep human connections because of race. The narrator uses this to highlight how society can teach people to ignore or “forget” meaningful relationships, much like how people ignore Blue’s emotions in the story. It’s a way to link the horse’s loneliness and loss to the human pain caused by slavery, showing how both involve a loss of empathy and understanding.

And about the Indians, considered to be ‘like animals’ by the ‘settlers’ (a very benign euphemism for what they actually were), who did not understand their description as a compliment.

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator reflects on the historical treatment of Native Americans (referred to as “Indians”) to further connect the story’s themes of dehumanization and misunderstanding.

The narrator thinks about how European settlers, who took over Native American lands, called Native people “like animals.” The term “settlers” is a soft, polite word that hides the reality of their actions as invaders who displaced and harmed Native communities. The settlers thought comparing Native Americans to animals was a neutral or even positive description, but the Native people didn’t see it that way—they understood it as an insult that stripped away their humanity. This shows a deep misunderstanding and disrespect, as the settlers failed to recognize Native Americans’ cultures, emotions, and rights, treating them as less than human.

In simple terms, this paragraph highlights how Native Americans were unfairly compared to animals by settlers, much like Blue, the horse, is misunderstood in the story. It connects the mistreatment of Native people to the way society ignores animals’ feelings, pointing out how both involve a lack of empathy and respect for others’ dignity. This ties into the broader theme of oppression across different groups, human and animal.

And about the thousands of American men who marry Japanese, Korean, Filipina, and other non-English-speaking women and of how happy they report they are, ‘blissfully’, until their brides learn to speak English, at which point the marriages tend to fall apart. What then did the men see, when they looked into the eyes of the women they married, before they could speak English? Apparently only their own reflections.

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator reflects on interracial marriages to explore themes of misunderstanding and superficial connections.

The narrator thinks about American men who marry women from countries like Japan, Korea, or the Philippines, where the women often don’t speak English at first. These men say they’re extremely happy, even “blissfully,” in the beginning. But once their wives learn to speak English and can express their own thoughts and personalities more clearly, the marriages often start to fall apart. The narrator wonders what these men saw when they looked into their wives’ eyes before they could speak English. The answer seems to be that the men only saw what they wanted to see—their own ideas or fantasies about these women—rather than truly understanding who they were.

In simple terms, this paragraph shows how some people build relationships based on assumptions rather than real connection, like seeing only their own reflection instead of the other person’s true self. This connects to the story’s theme of failing to recognize the emotions and depth of others, whether it’s Blue, the horse, or people who are different from us. It highlights how humans can ignore or misunderstand the feelings of others, just as they overlook Blue’s loneliness and pain.

I thought of society’s impatience with the young. ‘Why are they playing the music so loud?’ Perhaps the children have listened to much of the music of oppressed people their parents danced to before they were born, with its passionate but soft cries for acceptance and love, and they have wondered why their parents failed to hear.

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator reflects on society’s misunderstanding of young people, connecting it to broader themes of ignored emotions and overlooked messages.

The narrator thinks about how adults often get annoyed with young people, complaining, “Why are they playing their music so loud?” They suggest that maybe the kids are drawn to this music because it echoes the songs of oppressed groups—people who faced hardship and injustice—that their parents enjoyed before the kids were born. These songs carry deep, emotional pleas for love and acceptance, but they’re expressed quietly, with passion. The kids might wonder why their parents, who once danced to this music, didn’t truly hear or act on its message of compassion and fairness.

In simple terms, this paragraph is about how adults miss the point of what young people are expressing, just like society ignores Blue’s feelings in the story. The loud music represents the kids’ way of amplifying the cries for justice and love that their parents overlooked, tying into the story’s theme of failing to listen to the emotions and needs of others, whether it’s animals like Blue or marginalized groups.

I do not know how long Blue had inhabited his five beautiful, boring acres before we moved into our house; a year after we had arrived—and had also travelled to other valleys, other cities, other worlds—he was still there.

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator reflects on Blue’s ongoing presence in his confined field.

The narrator says they don’t know how long Blue, the white horse, had been living in his five-acre field, which is beautiful but dull, before they moved into their nearby house. A year after they arrived—and after they had gone on trips to other places like valleys, cities, and even far-off “worlds”—Blue was still there, stuck in the same small, fenced-in area.

In simple terms, this paragraph highlights how Blue’s life remains unchanged and limited, no matter how much time passes or what the narrator does. It emphasizes his ongoing loneliness and lack of freedom, setting up the story’s focus on his emotional struggles and the narrator’s growing awareness of them.

But then, in our second year at the house, something happened in Blue’s life. One morning, looking out the window at the fog that lay like a ribbon over the meadow, I saw another horse, a brown one, at the other end of Blue’s field. Blue appeared to be afraid of it, and for several days made no attempt to go near. We went away for a week. When we returned, Blue had decided to make friends and the two horses ambled or galloped along together, and Blue did not come nearly as often to the fence underneath the apple tree.

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator describes a significant change in Blue’s life.

During the second year of living in the house, something important happens to Blue, the white horse. One morning, the narrator looks out the window and sees a fog gently covering the meadow like a ribbon. In Blue’s field, they notice a new horse, a brown one, standing at the far end. At first, Blue seems scared of the brown horse and keeps his distance for a few days, not trying to approach it. The narrator and their partner then leave for a week-long trip. When they come back, they see that Blue has warmed up to the brown horse. The two horses are now friendly, walking or running together happily. Because of this new friendship, Blue doesn’t come to the fence by the apple tree as often as he used to, where the narrator would feed him apples.

In simple terms, this paragraph shows a hopeful moment in Blue’s lonely life when he gains a new companion, the brown horse. His initial fear turns into friendship, bringing him joy and reducing his dependence on the narrator’s apples. It highlights the importance of connection and sets up the story’s exploration of how relationships can change emotions, for both Blue and the narrator.

When he did, bringing his new friend with him, there was a different look in his eyes. A look of independence, of self-possession, of inalienable horseness. His friend eventually became pregnant. For months and months there was, it seemed to me, a mutual feeling between me and the horses of justice, of peace. I fed apples to them both. The look in Blue’s eyes was one of unabashed ‘this is fitness’.

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator describes how Blue’s new friendship with the brown horse changes his demeanor and deepens their own connection to the horses.

When Blue comes to the fence by the apple tree, he now brings his new friend, the brown horse, with him. The narrator notices a new expression in Blue’s eyes—one that shows confidence, calmness, and a strong sense of being truly himself, like he’s embracing his natural “horseness.” Later, the brown horse becomes pregnant, and for many months, the narrator feels a shared sense of fairness and peace with both horses, as if they’re all in harmony. The narrator continues to feed apples to both Blue and the brown horse, and Blue’s eyes have a clear, bold look that says, “This is how things should be.”

In simple terms, this paragraph shows how Blue’s new friendship makes him happier and more confident, like he’s found his place. The narrator feels a special bond with the horses, sensing a kind of justice and calm in their connection. Feeding them apples becomes a joyful routine, and Blue’s proud expression reflects the rightness of this moment, highlighting the story’s themes of companionship and emotional fulfillment.

It did not, however, last forever. One day, after a visit to the city, I went out to give Blue some apples. He stood waiting, or so I thought, though not beneath the tree. When I shook the tree and jumped back from the shower of apples, he made no move. I carried some over to him. He managed to half-crunch one. The rest he let fall to the ground. I dreaded looking into his eyes—because I had of course noticed that Brown, his partner, had gone—but I did look. If I had been born into slavery, and my partner had been sold or killed, my eyes would have looked like that. The children next door explained that Blue’s partner had been ‘put with him’ (the same expression that old people used, I had noticed, when speaking of an ancestor during slavery who had been impregnated by her owner) so that they could mate and she conceive. Since that was accomplished, she had been taken back by her owner, who lived somewhere else.

In this paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator describes a heartbreaking change in Blue’s life and connects it to human suffering.

The happy time with Blue and his friend, the brown horse, doesn’t last. One day, after returning from a trip to the city, the narrator goes to feed Blue apples. They expect him to be waiting eagerly near the apple tree, but he’s standing somewhere else, not moving toward the tree. When the narrator shakes the tree and apples fall, Blue doesn’t react or come closer. The narrator brings some apples to him, but Blue only half-eats one and lets the others drop to the ground, showing he’s not interested. The narrator is scared to look into Blue’s eyes because they’ve noticed that the brown horse, Blue’s companion, is gone. When they do look, Blue’s eyes are filled with such deep sadness and pain that the narrator compares it to how they might feel if they were enslaved and their loved one was sold or killed. The neighbor’s children explain that the brown horse was “put with” Blue—a phrase the narrator recognizes from stories of slavery, where it described enslaved women forced to have children with their owners—so that she could get pregnant. Once she was pregnant, her owner, who lived somewhere else, took her away.

In simple terms, this paragraph shows the devastating moment when Blue loses his friend, leaving him sad and withdrawn. His lack of interest in the apples and the pain in his eyes reveal his grief. The narrator connects Blue’s loss to the trauma of slavery, especially through the chilling phrase “put with,” highlighting how both animals and enslaved people were treated as property, with their emotions ignored. This deepens the story’s themes of loss, exploitation, and shared suffering.

Will she be back? I asked.

They didn’t know.

In this short exchange from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator asks about the brown horse’s fate and receives an uncertain response.

After learning that the brown horse, Blue’s companion, was taken away by her owner after becoming pregnant, the narrator asks the neighbor’s children, “Will she be back?” They respond that they don’t know, showing no clear answer or concern about what happened to her.

In simple terms, this brief moment highlights the uncertainty and indifference surrounding the brown horse’s removal. It underscores the lack of care for Blue’s emotional loss and the brown horse’s fate, reinforcing the story’s themes of exploitation and society’s tendency to overlook the feelings of animals. The narrator’s question shows their worry for Blue, while the vague reply deepens the sense of sadness and powerlessness in the situation.

Blue was ‘like a crazed person. Blue was, to me, a crazed person. He galloped furiously, as if he were being ridden, around and around his five beautiful acres. He whinnied until he couldn’t. He tore at the ground with his hooves. He butted himself against his single shade tree. He looked always and always towards the road down which his partner had gone. And then, occasionally, when he came up for apples, or I took apples to him, he looked at me. It was a look so piercing, so full of grief, a look so human, I almost laughed (I felt too sad to cry) to think there are people who do not know what animals suffer. People like me who have forgotten, and daily forget, all that animals try to tell us. ‘Everything you do to us will happen to you; we are your teachers, as you are ours. We are one lesson’ is essentially it, I think. There are those who never once have even considered animals’ rights: those who have been taught that animals actually want to be used and abused by us, as small children ‘love’ to be frightened, or women ‘love’ to be mutilated and raped… They are the great-grandchildren of those who honestly thought, because someone taught them this: ‘Women can’t think,’ and ‘niggers can’t faint.’ But most disturbing of all, in Blue’s large brown eyes was a new look, more painful than the look of despair: the look of disgust with human beings, with life; the look of hatred. And it was odd what the look of hatred did. It gave him, for the first time, the look of a beast. And what that meant was that he had put up a barrier within to protect himself from further violence: all the apples in the world wouldn’t change that fact.

In this powerful paragraph from Alice Walker’s “Am I Blue?”, the narrator vividly describes Blue’s intense emotional reaction to losing his companion, the brown horse, and reflects on the broader implications of animal suffering and human ignorance.

After the brown horse is taken away, Blue, the white horse, acts like he’s lost his mind, almost like a person overwhelmed with grief. He runs wildly around his five-acre field, as if someone is riding him, going in circles. He makes loud, desperate whinnying sounds until he’s too exhausted to continue. He digs at the ground with his hooves and rams himself into the only tree in his field that gives shade. He keeps staring down the road where the brown horse was taken, as if hoping she’ll return. Sometimes, when Blue comes to the fence for apples or the narrator brings apples to him, he looks at the narrator with eyes full of such deep sadness and pain that it feels almost human. This look is so intense that the narrator almost laughs, not because it’s funny, but because they’re too sad to cry. They’re struck by the realization that many people don’t understand how much animals like Blue suffer. The narrator admits they, too, had forgotten how animals express their feelings, just like people do every day. They believe animals are trying to teach us a lesson: “What you do to us will come back to you; we learn from each other, and we’re all part of the same lesson.” Some people, though, never even think about animals’ rights. They’ve been taught wrong ideas, like animals enjoy being used or hurt, similar to old, harmful beliefs that women can’t think or Black people can’t feel pain. The most upsetting thing is a new look in Blue’s big brown eyes—beyond sadness, it’s a look of disgust and hatred toward humans and life itself. This hatred changes him, making him seem like a wild “beast” for the first time. This new behavior shows Blue has built an emotional wall to protect himself from more hurt, and no amount of apples can undo that pain.

In simple terms, this paragraph shows Blue’s heartbreak after losing his friend, acting out in frantic, almost human ways to express his grief. His pain makes the narrator see how much animals feel, just like people, and how society often ignores this. Blue’s new look of hatred reflects his distrust of humans after being hurt, connecting to the story’s themes of empathy, loss, and the consequences of cruelty, while also linking animal suffering to historical human injustices.

And so Blue remained, a beautiful part of our landscape, very peaceful to look at from the window, white against the grass. Once a friend came to visit and said, looking out on the soothing view: ‘And it would have to be a white horse; the very image of freedom.’ And I thought, yes, the animals are forced to become for us merely ‘images’ of what they once so beautifully expressed. And we are used to drinking milk from containers showing ‘contented’ cows, whose real lives we want to hear nothing about, eating eggs and drumsticks from ‘happy’ hens, and munching hamburgers advertised by bulls of integrity who seem to command their fate.

Walker describes Blue, the white horse, standing in the field, looking calm and beautiful from her window. He blends into the landscape like a picturesque part of nature. This shows how people can view animals as just a pleasant sight, ignoring their inner lives or struggles.

A friend visits and sees Blue, commenting that a white horse is the perfect “image of freedom.” The friend sees Blue as a symbol of something noble and free, like in stories or paintings, rather than as a real horse with emotions. This highlights how humans often project their own ideas—like freedom—onto animals without understanding their actual experiences.

Walker reflects on her friend’s comment and realizes that humans often reduce animals to mere symbols or stereotypes. Instead of seeing animals for who they truly are—beings with feelings like loneliness or pain—we turn them into simplified “images” that make us feel good or serve our purposes. Blue, for example, isn’t free; he’s confined and grieving, but people see only the pretty picture.

Walker extends this idea to how we consume animal products. She points out that milk cartons show “contented” cows, egg packages feature “happy” hens, and hamburger ads use proud-looking bulls. These images make us think the animals are okay with being used, but in reality, we don’t want to know about their suffering—cramped cages, forced milking, or slaughter. We prefer the comforting lies over the harsh truth of their lives.

In short, this paragraphs is about how humans disconnect from the real emotions and suffering of animals. We see them as symbols (like Blue as “freedom”) or as products (like “happy” cows), ignoring their pain and individuality to make ourselves feel better about using them. Walker’s point is that this blindness prevents us from truly understanding animals and their experiences.

As we talked of freedom and justice one day for all, we sat down to steaks. I am eating misery, I thought, as I took the first bite. And spit it out.

In this final paragraph of Alice Walker’s Am I Blue?, the author brings her reflections on animal suffering and human disconnection to a powerful, personal conclusion.

While discussing big ideas like freedom and justice for everyone, Walker and her companions sit down to eat a meal of steaks. As she takes her first bite, she’s struck by a sudden realization: the meat comes from an animal, likely one that suffered greatly, much like Blue, the horse whose loneliness and grief she witnessed. She thinks, “I am eating misery,” meaning she’s consuming the pain and suffering of a living creature. This thought is so overwhelming that she can’t continue—she spits out the bite, rejecting the act of eating something tied to such cruelty.

This moment ties together the essay’s themes. Walker’s experience with Blue has opened her eyes to the emotional lives of animals and the ways humans ignore their suffering, whether through slavery-like exploitation (like Blue’s partner being taken away) or through the food industry’s “happy” animal images. Her rejection of the steak is a personal stand against participating in that misery, showing how her newfound awareness changes her actions. It’s a call to recognize the connection between our choices—like eating meat—and the suffering they may cause, urging us to live more consistently with the values of freedom and justice we claim to hold.

Word Meaning

| Word | English Meaning | Hindi Meaning |

| Companion | A person or animal one spends time with | साथी, संग-साथी |

| Meadow | A field of grass or wildflowers | घास का मैदान |

| Deck | A flat platform outside a house, often made of wood | डेक, एक प्रकार का लकड़ी का प्लेटफ़ॉर्म |

| Mane | Long hair on the neck of a horse | घोड़े का जुरा |

| Ambling | Walking at a slow, relaxed pace | धीरे-धीरे चलना |

| Boarded | Kept and cared for temporarily (usually animals) | अस्थायी रूप से पालना, रखने के लिए |

| Stocky | Short and broad in build | तगड़ा और चौड़ा |

| Furiously | In a very angry, intense, or fast way | ज़ोर-ज़ोर से, क्रोधी या तीव्र रूप से |

| Get off | To dismount or come down from (a horse or vehicle) | उतरना |

| Flanks | The sides of an animal’s body between ribs and hips | शरीर का पार्श्व भाग (पेट और कूल्हों के बीच) |

| Relished | Enjoyed greatly | आनंद लिया, पसंद किया |

| Succulent | Juicy and tender | रसदार, रसीला |

| Stumbled | Trip or momentarily lose balance while walking | लड़खड़ाना, ठोकर खाना |

| Munching | Eating something steadily and audibly | चबाना, मुँह से आवाज़ करते हुए खाना |

| Stalks | The main stems of plants | तना, पौधे का मुख्य डंठल |

| Whinny | The sound a horse makes | घोड़े की आवाज़, हिननी |

| Snort | To make a sudden explosive sound through the nose | सूंघना, नाक से जोरदार आवाज़ करना |

| Stamp | To strike the ground forcefully with the foot | ज़मीन पर पैर पटकना |

| Crunched | Made a loud crushing sound by biting or stepping | चबाना, क्रंच की आवाज़ करना |

| Broad-breasted | Having a wide chest | चौड़ा छाती वाला |

| Enormity | The great size or extent | बहुत बड़ा आकार या महत्व |

| Spooked | Frightened suddenly or scared away | डर जाना, डराकर भाग जाना |

| Tramp | Walk heavily or noisily | भारी कदमों से चलना |

| Wander | Walk or move around without a fixed purpose | घूमना, टहलना |

| Forthcoming | About to happen or appear | आने वाला, उपलब्ध |

| Piece (a quilt) | To join small pieces of cloth together | जोड़ना (कपड़ों के टुकड़े) |

| Squares | The small blocks used in quilting | चौकोर टुकड़े (कपड़ों के) |

| Slavery | The system of owning people as property | दासता, गुलामी |

| Mammy | A black woman who cared for white children during slavery | दासी (विशेष रूप से गुलामी के समय देखभाल करने वाली) |

| Settlers | People who move to a new area to live | बसने वाले, उपनिवेशक |

| Euphemism | A mild or indirect word substituted for one considered harsh | सौम्य शब्द, कोमल भाषा |

| Blissfully | Happily, without worries | आनंदपूर्वक, सुखी |

| Reflections | Images seen in a mirror or water | प्रतिबिंब, परछाई |

| Oppressed | Kept down by unjust power or authority | दबाया हुआ, अत्याचार झेलना |

| Ambled | Walked slowly and leisurely | धीरे-धीरे टहलना |

| Galloped | Ran fast, like a horse | दौड़ा (घोड़े की तरह तेज दौड़) |

| Self-possession | Calm control of oneself | आत्म-संयम, आत्म-नियंत्रण |

| Inalienable | Impossible to take away or give up | अविभाज्य, छीन न सकने वाला |

| Horseness | The qualities or nature of a horse | घोड़े जैसी प्रकृति |

| Mutual | Shared by two or more parties | पारस्परिक, साझा |

| Unabashed | Not embarrassed or ashamed | निडर, बिना झिझक के |

| Half-crunch | Partially crushed or bitten | आधा चबाया हुआ |

| Ancestor | A person from whom one is descended | पूर्वज, पूर्वजों |

| Impregnated | Made pregnant | गर्भवती बनाया गया |

| Conceive | To become pregnant | गर्भधारण करना |

| Crazed | Mentally disturbed or insane | पागल, मानसिक रूप से विक्षिप्त |

| Whinnied | Made a whinny sound (horse’s sound) | हिननी की आवाज़ देना |

| Tore | Ripped or pulled apart | फाड़ना, छिन्न-भिन्न करना |

| Hooves | The hard feet of animals like horses | खुर |

| Butted | Hit or pushed with the head | सिर से ठोकर मारना |

| Piercing | Very sharp or intense | तीव्र, चुभन वाला |

| Grief | Deep sorrow or distress | शोक, गहरा दुख |

| Mutilated | Severely damaged or injured | विकृत, बुरी तरह क्षतिग्रस्त |

| Niggers | A racial slur (offensive term) | नस्लीय अपशब्द (अशिष्ट शब्द) |

| Despair | Complete loss of hope | निराशा, हताशा |

| Disgust | Strong dislike or revulsion | घृणा, मतली |

| Hatred | Intense dislike or ill will | नफ़रत |

| Beast | A wild animal or a cruel person | जानवर, जंगली प्राणी / क्रूर व्यक्ति |

| Barrier | Something that blocks or separates | बाधा, अवरोध |

| Soothing | Having a calming or comforting effect | सुखदायक, शान्तिदायक |

| Landscape | The visible features of an area of land | दृश्य, परिदृश्य |

| Contented | Happy and satisfied | संतुष्ट, प्रसन्न |

| Drumsticks | The lower part of a chicken leg used as food | मुर्गे की टांग का हिस्सा |

| Munching hamburgers | Eating hamburgers noisily | बर्गर चबाना |

| Bulls of integrity | Bulls symbolizing honesty and strength | ईमानदारी और शक्ति वाले बैल |

| Misery | Great suffering or unhappiness | दुख, कष्ट |

| Spit | To eject saliva forcibly from the mouth | थूकना |

| Companion | A person or animal one spends time with | साथी, संग-साथी |

Characters

Blue, the White Horse

Blue is the emotional heart of the story, a large white horse confined to a small five-acre fenced field. His expressive eyes reveal a wide range of feelings—loneliness, boredom, joy, grief, anger, and disgust. Blue’s life is marked by confinement and isolation, wandering aimlessly and often begging for apples from the narrator. When a brown horse arrives, Blue becomes lively and proud, showing his “inalienable horseness.” However, after she is taken away by her owner, Blue’s behavior turns frantic and sorrowful, reflecting deep pain and distrust toward humans. Blue challenges the idea that animals lack complex emotions, and his suffering mirrors human experiences of loss and oppression. His name and tears echo the song “Am I Blue?” emphasizing his silent plea for understanding and empathy.

The Narrator

The unnamed narrator observes Blue’s life and reflects on the broader meaning of his emotions and experiences. Initially detached but curious, the narrator watches Blue closely and relates his feelings to human history, including slavery and colonization. The narrator admits to having forgotten how animals communicate feelings, but Blue’s grief rekindles their empathy. Over time, the narrator becomes more self-aware and willing to change, culminating in the rejection of meat, which symbolizes a deeper recognition of animal suffering. Through the narrator’s journey, the story speaks to people who have lost touch with animal emotions and encourages a renewed awareness and compassion.

The Brown Horse

Though a minor character, the brown horse plays an important role as Blue’s companion. She quickly bonds with Blue and brings joy and confidence to his life. Despite this, she has no control over her fate—brought to Blue for breeding and removed once pregnant. Her treatment exposes the cruelty of viewing animals as property and tools for human use. The brown horse symbolizes exploited beings, especially those forced into reproductive roles, and her disappearance is central to Blue’s heartbreak and the narrator’s deepening understanding of suffering.

The Neighbors’ Children

The children next door who occasionally ride Blue and explain the brown horse’s fate act with casual detachment. They show little concern for Blue’s feelings, riding him briefly and then disappearing for weeks. Their matter-of-fact description of the brown horse being “put with” Blue to breed reflects a societal attitude that normalizes animal exploitation and ignores their sentience. The children represent the process of “forgetting” animal emotions that society perpetuates, standing in contrast to the narrator’s growing empathy.

The Friend

A visiting friend comments on Blue, calling him “the very image of freedom,” while missing the horse’s pain and confinement. This friend embodies society’s tendency to romanticize animals based on surface appearances rather than recognizing their real suffering. Their superficial view prompts the narrator to reflect on the gap between image and reality, reinforcing the story’s critique of human ignorance and misplaced ideals.

The Owners of Blue and the Brown Horse

Although they do not appear directly, the owners hold control over Blue and the brown horse. Blue’s owner boards him with neighbors and lives elsewhere, while the brown horse’s owner uses her for breeding and removes her once she is pregnant. These distant, exploitative figures symbolize broader systems of oppression, treating animals as property without regard for their feelings. Their control causes Blue’s suffering and highlights parallels between animal exploitation and human injustices like slavery and colonization.

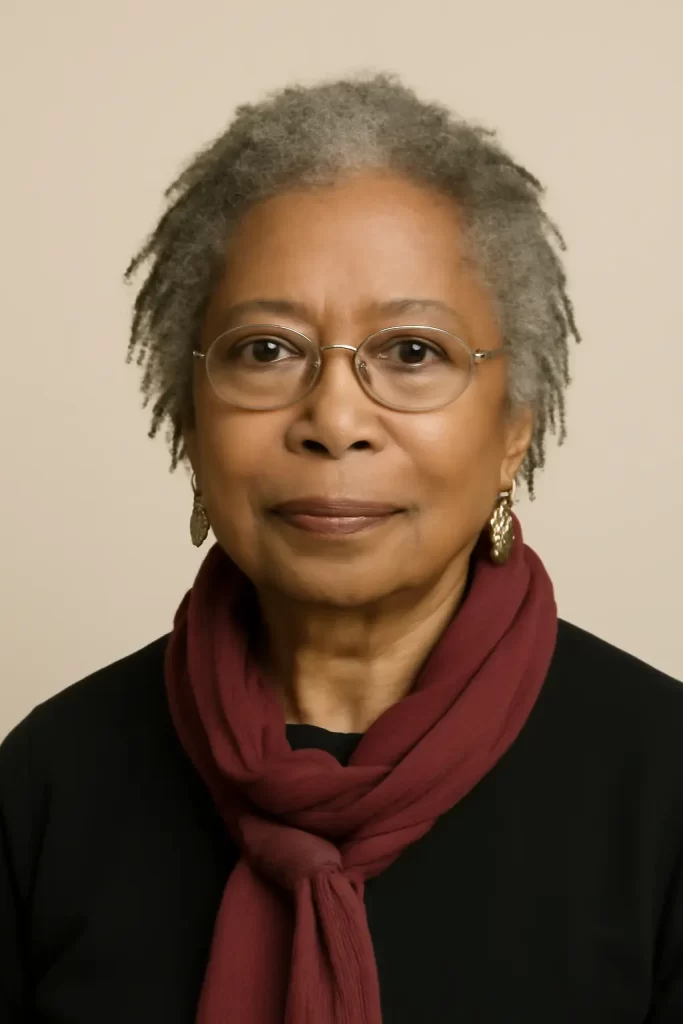

Alice Walker

Early Life and Education

Alice Malsenior Walker was born on February 9, 1944, in Eatonton, Georgia, the youngest of eight children in a Black sharecropping family. At eight, she suffered an injury when her brother accidentally blinded her right eye with a BB gun, leading to shyness and social isolation during childhood. Despite this, Walker excelled academically, becoming high school prom queen and valedictorian. She developed a lifelong passion for reading and writing poetry.

In 1961, Walker earned a scholarship to Spelman College in Atlanta, where she became active in the civil rights movement. She later transferred to Sarah Lawrence College in New York, continuing her activism and studies. During this period, she attended the Youth World Peace Festival in Finland and met Martin Luther King Jr., reflecting her deepening commitment to social justice.

Early Career and Activism

After graduating from Sarah Lawrence in 1965, Walker married Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal, a white civil rights lawyer, and moved to Jackson, Mississippi. She worked as a Black history consultant and served as writer-in-residence at Jackson State and Tougaloo Colleges. Her activism continued alongside her writing career, culminating in the publication of her first novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland (1969). In 1977, following her divorce, Walker relocated to Northern California, where she continues to write.

Poetry and Short Fiction

Walker’s first poetry collection, Once (1968), drew from her civil rights experiences and personal struggles, including an unwanted pregnancy and abortion. Influenced by haiku and existential philosophy, the poems balance themes of despair and renewal. Her subsequent collections, such as Revolutionary Petunias (1973) and Good Night, Willie Lee (1979), explore her southern heritage and political consciousness, earning accolades like the Lillian Smith Book Award.

Her short stories, notably In Love and Trouble: Stories of Black Women (1973) and You Can’t Keep a Good Woman Down (1982), vividly portray Black women’s struggles with social expectations, violence, and resilience. Early recognition came with “To Hell with Dying,” included in Langston Hughes’s anthology of Black short stories.

Major Novels and Literary Achievements

Alice Walker gained international acclaim with The Color Purple (1982), a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel that depicts the life of Celie, a Black woman overcoming abuse and discovering self-worth through a community of women. The novel’s powerful themes of female empowerment and racial injustice have inspired film and Broadway adaptations.

Other important novels include Meridian (1976), about civil rights activism; The Temple of My Familiar (1989); and Possessing the Secret of Joy (1992), which examines female genital mutilation. Her later works, such as By the Light of My Father’s Smile (1998) and Now Is the Time to Open Your Heart (2004), continue exploring spirituality, identity, and aging.

Essays, Womanism, and Activism

Walker’s essay collections, including In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (1983), introduced “womanism,” a framework celebrating Black women’s creativity, strength, and emotional resilience. Her essays often explore feminism, race, identity, and animal rights, reflecting her broad activism.

Notably, in Living by the Word (1988), Walker expresses concern for animal welfare and nature, with her essay “Am I Blue?” highlighting the suffering of animals and marking her transition toward vegetarianism. Her political activism extends to environmentalism, anti-nuclear campaigns, and international women’s rights, including opposition to female genital mutilation and support for Palestinian causes.

Legacy and Recognition

Alice Walker’s prolific career spans poetry, novels, short fiction, and essays, firmly establishing her as a vital voice in American literature and activism. She has taught at major universities, contributed to important literary journals, and revived interest in African American literary figures such as Zora Neale Hurston.

In 2001, Walker was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame. Her personal and literary archives are housed at Emory University, ensuring her enduring influence on literature, civil rights, feminism, and animal advocacy.

Themes

1. Loneliness and Isolation

Blue, the white horse, is confined to a small five-acre fenced field, a limited space that symbolizes both physical and emotional isolation. Despite the meadow’s natural beauty, Blue’s confinement leads to boredom and profound loneliness. His restless behavior—wandering aimlessly, whinnying, and sometimes harming himself—reveals the deep psychological impact of isolation. Walker uses Blue’s situation to illustrate how captivity strips away freedom and companionship, causing suffering not only in humans but in animals as well.

2. Empathy and Communication Across Species

Walker powerfully conveys that animals possess complex emotional lives and can communicate feelings through their behavior and expressions. Blue’s eyes, in particular, serve as windows into his loneliness, grief, and even hatred after his companion’s removal. The narrator reflects on how adults often forget this ability to “read” animals’ emotions, while children naturally understand it. The story calls readers to rediscover empathy and recognize the emotional realities of nonhuman beings, emphasizing that animals are not mere objects but sentient creatures capable of rich inner lives.

3. Oppression and Loss

Blue’s experience of losing his companion horse parallels human histories of forced separation, trauma, and loss, such as those endured during slavery and colonialism. Walker draws explicit connections between the horse’s grief and the pain of enslaved people whose families were torn apart. The language used by the neighbors, like “put with him,” echoes the dehumanizing terms of slavery. This theme extends to broader reflections on systemic oppression, showing how violence and control harm both humans and animals, making Blue’s story a universal metaphor for suffering under domination.

4. Human Hypocrisy and Indifference

Walker critiques society’s tendency to romanticize animals as symbols—like Blue as the “image of freedom”—while simultaneously ignoring or perpetuating their real suffering. The neighbors’ casual treatment of Blue and the brown horse as breeding property, the friend’s shallow admiration of Blue’s beauty, and the narrator’s own conflicted act of eating steak highlight a deep hypocrisy. Humans often want to enjoy the idea of animals without confronting the ethical consequences of their exploitation, demonstrating widespread indifference to animal welfare and suffering.

5. Connection and Compassion as a Path to Change

The narrator’s relationship with Blue evolves from detached observation to deep empathy and ethical awakening. Through feeding Blue apples and witnessing his pain, the narrator reconnects with a childhood awareness of animals’ emotional depth. This growing compassion leads to a critical self-reflection about human complicity in cruelty, exemplified by the narrator’s refusal to eat meat. Walker suggests that meaningful change begins with recognizing shared vulnerability and suffering, urging readers to expand their circle of compassion beyond their own species.

Style

1. Narrative Voice and Tone

Walker employs a first-person reflective narrative voice that blends personal anecdote with social commentary. The tone is intimate and contemplative, inviting readers into the narrator’s evolving awareness of Blue’s emotional life and broader ethical issues. At times, the voice is tender and empathetic, while in other moments it sharpens into quiet critique, especially when addressing human indifference or hypocrisy. This shifting tone creates an engaging and honest dialogue between narrator and reader.

2. Use of Imagery

The story is rich in vivid and sensory imagery, particularly centered around Blue and his environment. Descriptions of Blue’s physicality—his “huge, cubelike teeth,” “flexible dark lips,” and “large brown eyes”—bring the horse vividly to life and emphasize his sentience. The meadow, apple tree, and natural surroundings contrast with Blue’s confinement, underscoring themes of freedom versus captivity. Images of Blue’s restless galloping and self-harm evoke powerful emotions and highlight his internal suffering.

3. Symbolism

Walker uses Blue symbolically to represent broader themes of freedom, oppression, and emotional suffering. The white horse becomes a living metaphor for the plight of both animals and humans subjected to control and loss. The apples, repeatedly offered by the narrator, symbolize small acts of kindness and connection but also the limits of comfort within captivity. Blue’s changing gaze—from loneliness to grief to hatred—functions as a symbolic barometer of trauma and resilience.

4. Blending of Genres: Essay and Narrative

Am I Blue? straddles the line between personal essay, short story, and social critique. Walker’s blending of genres allows for both storytelling and philosophical reflection, making the piece intellectually and emotionally rich. The narrative unfolds with story-like details and character interactions but is interspersed with broader meditations on slavery, animal rights, and human empathy. This hybrid style deepens the work’s impact and accessibility.

5. Language and Diction

Walker’s language is clear, evocative, and accessible, yet deeply poetic in moments. She balances straightforward description with lyrical passages that invite emotional resonance. Colloquial phrases—such as “put with him”—carry weight by evoking historical trauma and everyday cruelty. The repetition of certain motifs and phrases (like the tears in Blue’s eyes) lends a rhythmic quality that reinforces emotional themes.

6. Emotional Appeal and Ethical Reflection

The style skillfully engages readers’ emotions by personifying Blue’s feelings while simultaneously provoking ethical reflection. Walker’s narrative encourages readers to see Blue not just as an animal but as a sentient being capable of suffering, thereby expanding the story’s moral reach. The use of empathy as a narrative tool invites readers to reconsider their own relationship with animals and injustice.

Symbolism

1. Blue, the White Horse

Blue himself is the central symbol of the story. As a large, beautiful white horse, he represents more than just an animal; he embodies the concepts of freedom, captivity, and emotional depth. White often symbolizes purity and liberty, yet Blue’s confinement to a small fenced area contrasts sharply with this ideal, highlighting the painful gap between appearance and reality. His emotional journey—from loneliness to joy, then to grief and hatred—mirrors human experiences of oppression and trauma, making him a powerful metaphor for all beings subjected to control and suffering.

2. The Meadow and the Fence

The expansive meadow visible from the narrator’s window symbolizes natural freedom and possibility. However, Blue’s limitation to only a small fenced-in portion of it serves as a poignant symbol of restricted liberty. This fence acts as a barrier—not only physical but psychological—representing the constraints imposed by humans on animals, and metaphorically, the social, racial, and cultural boundaries that confine human lives.

3. Apples

The apples the narrator feeds Blue function as a symbol of kindness and limited comfort. They represent small acts of compassion that provide temporary relief but cannot replace true freedom or companionship. The apples also signify human control—Blue’s dependence on these treats reflects the imbalance of power between humans and animals. The ritual of feeding apples deepens the connection between Blue and the narrator but also underscores the limitations of such gestures.

4. Blue’s Eyes

Blue’s eyes are perhaps the most poignant symbol in the story. Described as deeply expressive and “so human,” they reflect his inner emotional world—his loneliness, grief, and eventual hatred. The eyes symbolize the window to the soul, challenging readers to confront the sentience and suffering of animals. They also serve as a mirror to human pain, linking Blue’s experiences with historical human oppression, such as slavery.

5. Blue’s Companion, the Brown Horse

The brown horse symbolizes hope, connection, and the possibility of healing. Her arrival brings joy and revitalization to Blue’s confined life, symbolizing companionship and freedom’s brief return. However, her removal for breeding purposes becomes a symbol of exploitation and the cruel interruption of natural bonds, emphasizing how freedom and happiness are often denied by human control.

6. The Road

The road down which Blue’s companion leaves becomes a symbol of loss and separation. It represents the irreversible distance between Blue and his friend and the pain of forced parting. The road also serves as a metaphor for the path of trauma and the unknown future after loss, emphasizing themes of grief and abandonment.

7. Steak on the Table

At the story’s conclusion, the steak that the narrator spits out symbolizes human complicity in animal suffering. It is a stark, uncomfortable symbol of how people consume and profit from the misery of animals while simultaneously discussing ideals like justice and freedom. The steak represents hypocrisy and the ethical crisis at the heart of human-animal relationships.

Am I Blue by Alice Walker Questions and Answers

Very Short Answer Questions

What is the name of the horse in the story?

Blue.

Where does the narrator live?

In a rented country house next to a meadow.

What does the narrator feed Blue?

Apples.

What color is Blue?

White.

Who is Blue’s companion for a short time?

A brown horse.

Why is the brown horse taken away?

She was used for breeding and her owner took her back.

How does Blue react when his companion leaves?

He gallops wildly and shows grief and anger.

What does the narrator realize about animals?

They communicate emotions like humans.

What historical oppression does the narrator compare Blue’s pain to?

Slavery.

What does the narrator spit out at the end?

Steak.

Why does the narrator reject the steak?

They feel it’s “eating misery.”

What does Blue’s name symbolize?

His sadness, tied to the song “Am I Blue?”

What does the meadow represent?

The illusion of freedom.

What do the apples symbolize?

Fleeting care that can’t heal deep pain.

What does Blue’s fence symbolize?

Confinement and isolation.

What emotion does Blue show after losing his companion?

Grief, disgust, and hatred.

Who calls Blue “the very image of freedom”?

The narrator’s friend.

What literary style does Walker use in the story?

Lyrical and reflective prose.

What broader issue does the story link to animal suffering?

Human oppression, like racism and sexism.

What does the narrator learn from Blue?

To empathize with animals and reject exploitation.

Short Answer Questions

What are the physical features of Blue before which the narrator feels small?

In Am I Blue by Alice Walker, the narrator feels physically small beside Blue’s imposing stature. Blue’s “high, broad-breasted enormity” emphasizes his large and powerful frame. The narrator is fascinated by Blue’s “flexible dark lips” and “huge, cubelike teeth” that crunch apples “core and all,” highlighting his strength and majesty. His white coat and the way he flips his flowing mane while cropping grass add to his graceful yet commanding presence. This grandeur contrasts with the narrator’s human scale, evoking awe and humility. Blue’s physicality symbolizes his emotional depth, making his later suffering all the more impactful.

Why does the narrator prefer walking to riding on horseback?

The narrator prefers walking because of a traumatic childhood incident. Their brother spooked their horse, Nan, which caused the narrator to be thrown “head first, against the trunk of a tree.” This frightening accident ended their riding experience, reinforced by their mother’s concern. The trauma instilled a lasting fear, leading the narrator to choose walking over horseback riding. This personal history reflects a disconnection from animals, which Blue’s expressive eyes later help the narrator to rediscover, symbolizing lost bonds with nature and animals.

What feelings were evoked in the narrator by the bored expression of the horse in summer?

Blue’s bored expression during the dry summer, as he “munches dried stalks half-heartedly,” evokes deep sympathy in the narrator. The horse’s evident loneliness and limited environment stir recognition and compassion. The narrator recalls childhood memories of riding horses, feeling “thrilled as a child” by Blue’s presence despite his boredom. This leads them to feed Blue apples, sparking a bond and opening reflections on animals’ emotional lives. Walker uses Blue’s summer boredom to highlight animal sentience and the pain of confinement.

Why does the writer call animals completed creations?

Walker calls animals “completed creations” because, unlike humans, animals fully express their nature and emotions without pretense or change. The narrator observes that animals “are not likely to change” because it is their nature to express themselves honestly—whether through grief, joy, or loneliness—as seen in Blue’s eyes. This contrasts with humans, who often suppress or forget such communication as they grow older. The phrase underscores Walker’s belief in animals’ sentience and emotional integrity, a key message in her animal rights advocacy and writings like Living by the Word.

What change did the arrival of a brown companion bring in Blue’s attitude?

The arrival of the brown horse transforms Blue’s attitude from loneliness to joy and vitality. Initially cautious, Blue soon bonds with her, and they “ambled or galloped along together.” The narrator notices a “look of independence, of self-possession, of inalienable horseness” in Blue’s eyes, signifying pride and happiness. This companionship relieves Blue’s boredom, emphasizing his capacity for emotional connection. This positive change sets up a poignant contrast with the devastation Blue experiences when she is taken away.

Why did Blue stop eating apples? What more changes followed in him?

Blue stops eating apples after the brown horse is taken away because his grief overwhelms him. He “managed to half-crunch one” apple and let the rest fall, showing his loss of appetite and spirit. Following this, Blue becomes frantic—galloping “furiously,” whinnying until hoarse, and butting his head against a tree. His eyes reveal “a look so piercing, so full of grief,” evolving into “disgust with human beings” and “hatred.” He becomes a “beast,” erecting an emotional barrier to protect himself. These changes highlight Walker’s theme of the deep psychological impact of loss and trauma on sentient beings.

‘All the apples in the world would not change that fact,’ says the narrator. What fact?

The “fact” is Blue’s enduring grief and distrust following the brown horse’s removal. No amount of kindness—symbolized by apples—can heal the deep emotional wound caused by loss and human cruelty. The narrator sees Blue’s “look of disgust with human beings, with life; the look of hatred” as a protective barrier that prevents further suffering but also isolates him. This statement emphasizes the limits of superficial comfort in addressing profound pain, reflecting Walker’s critique of systemic exploitation.

‘Looking out the window at the fog that lay like a ribbon over the meadow, I saw another horse.’ What figure of speech has been used here?

This is a simile, comparing the fog to a “ribbon” using the word “like.” The phrase “the fog that lay like a ribbon over the meadow” evokes a delicate, flowing image that enhances the tranquil yet somber atmosphere. It sets the stage for the brown horse’s arrival, symbolizing a brief moment of beauty and hope before later loss.

What does the narrator’s friend’s comment about Blue reveal about societal ignorance?

The friend calls Blue “the very image of freedom,” which reveals a societal tendency to romanticize animals superficially without recognizing their real suffering. The friend’s comment overlooks Blue’s confinement and grief, mirroring common ignorance about animal exploitation. This reflects Walker’s theme of how society reduces animals to symbols or “images” rather than acknowledging their sentience, prompting the narrator’s realization about the hypocrisy in attitudes toward animals.

How does the story’s setting contribute to its themes?